Summary

The number of species at risk of extinction continues to rise. As at 2020–21, 1,043 species and 115 ecological communities are listed as threatened under NSW legislation including 78 species declared extinct.

Why species and habitat are important

There has been a general pattern of decline in species diversity in NSW since European settlement. Some species of plants and animals, including fish, are at risk of extinction due to threatening processes such as removal of habitat. Conservation of threatened species is important to stabilise this loss of biodiversity. Programs such as Saving our Species are working to increase the number of species that will be secure in the wild for 100 years.

Aboriginal people attribute tremendous spiritual, cultural or symbolic value to many animals, plants and ecological communities, a value that is critical to identity and relationship with Country. The protection of these species and communities is fundamentally important in maintaining Aboriginal culture, language and knowledge.

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of threatened species, communities and populations |

|

Getting worse | ✔✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are defined in .

Status and Trends

In NSW in the three years to December 2020, the number of listings of threatened species increased by 18 (or 2%), with 1,043 species listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation and Fisheries Management Acts (Spotlight figure 11).

The number of plants and animals and communities being managed under the Saving our Species program has steadily increased, with 465 projects in 2018–19 covering roughly 40% of the listed species, communities and populations in NSW.

However, modelling in the assessment of the NSW Biodiversity Indicator Program (BIP) predicts that only 496 or 50% of the 991 terrestrial species listed as threatened are predicted to survive in 100 years’ time (). Management and conservation efforts will not be enough to save many species without addressing key threats such as habitat removal and climate change.

Spotlight figure 11: Total listings of threatened species 1995–2020

Pressures

A total of 47 key threatening processes have been identified as threatening the survival of species, communities and populations – 39 mainly terrestrial threats and eight aquatic. The most common threats are habitat loss due to the clearing and degradation of native vegetation and the spread of invasive pests and weeds. The capacity of species to adapt to these pressures is further constrained by climate change.

Altered fire regimes impact the ability of plant species and communities to regenerate or repropagate and extreme wildfires can decimate local animal populations. Water extraction and altered river flows and cycles affect a range of aquatic and bird species.

Response

The Saving our Species (SoS) program is the NSW Government’s commitment to improve the future of threatened species and ecological communities in the wild for the next 100 years. In May 2018, the government released the NSW Koala Strategy to help secure the future of koalas in the wild.

Biodiversity legislation in NSW to protect threatened species includes the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, Fisheries Management Act 1994 and the Common Assessment Method for national listing of threatened species.

Public national parks and reserves, the foundation of conservation efforts in NSW, play a vital role in protecting habitat and providing refuge for many threatened species that are sensitive to habitat disturbance. Threatened species are also increasingly being conserved on privately-owned land.

There are opportunities to further reintroduce locally extinct mammals in managed areas free of invasive species such as foxes and cats, and assess longer term impacts of legislative changes on threatened species and their natural habitats.

There is a need to learn more about how Aboriginal cultures and practices improve the care, protection and management of species, their habitats and the overall environment. This includes qualitative data collection, oral stories and Aboriginal cultural knowledge. In this respect, the EPA Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group recommends that significant Aboriginal cultural species be included as an indicator for future State of the Environment reporting.

Related topics: | | | | | |

Context

The NSW landscape is not in pristine condition. Changes to our landscapes create new environments and provide food and materials. These changes also alter habitats and may make them less suitable for biodiversity ().

Overall, there has been a general pattern of decline in species diversity in NSW since European settlement (; ; ). Conservation of threatened species is important to stabilise this loss of biodiversity.

The NSW approach to conserving threatened species emphasises protecting the species at greatest risk of extinction. Tracking the progress of threatened species in NSW is indicative of the overall status of species diversity and may be used as an indicator of the effectiveness of programs to conserve biodiversity and save threatened species.

Aboriginal people attribute tremendous spiritual, cultural or symbolic value to many animals, plants and ecological communities, a value that is critical in their identity and relationship with Country. The protection of these cultural and spiritual assets is fundamentally important to maintaining Aboriginal culture, language and knowledge.

Status and Trends

Threatened species listings

This topic describes the status of native plant and animal species listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act) or the Fisheries Management Act 1994 (FM Act). For a broader discussion on using the outcomes for species, primarily land-based vertebrate animals, as a surrogate for biodiversity, go to the topic.

At 31 December 2020, a total of 1,043 species were listed as threatened in NSW under the BC Act and FM Act (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1: Number of NSW species listed as threatened species in NSW under the Biodiversity Conservation and Fisheries Management Acts at 31 December 2020

| Taxon grouping | Total no. of NSW native species | Total no. of species listed | % of species listed | Presumed extinct | Critically endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammals (terrestrial) | 138 | 83 | 60% | 26 | 3 | 15 | 39 |

| Marine mammals | 40 | 7 | 18% | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Birds | 452 | 140 | 31% | 14 | 12 | 21 | 93 |

| Amphibians | 83 | 29 | 35% | 0 | 5 | 13 | 11 |

| Reptiles | 230 | 45 | 20% | 1 | 1 | 21 | 22 |

| Plants (terrestrial) | 4,677 | 671 | 14% | 32 | 79 | 330 | 230 |

| Aquatic plants and algae | n/a | 2 | n/a | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Freshwater fish | 60 | 11 | 18% | 0 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| Marine fish, sharks and rays | n/a | 8 | n/a | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Invertebrates (terrestrial) | n/a | 24 | n/a | 1 | 6 | 17 | 0 |

| Aquatic invertebrates | n/a | 12 | n/a | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Fungi and algae | n/a | 11 | n/a | 0 | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| Total | n/a | 1,043 | n/a | 78 | 116 | 439 | 411 |

Notes:

n/a - Numbers not available

At 31 December 2020, a total of 75 populations were listed as threatened in NSW under the Biodiversity Conservation and Fisheries Management Acts (Table 11.2).

Table 11.2: Number of NSW populations listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation and Fisheries Management Acts as at 31 December 2020

| Taxon grouping | Endangered populations |

|---|---|

| Mammals (terrestrial) | 13 |

| Birds | 7 |

| Amphibians | 1 |

| Reptiles | 1 |

| Plants (terrestrial) | 29 |

| Aquatic plants and algae | 1 |

| Freshwater fish | 4 |

| Invertebrates (terrestrial) | 1 |

| Total | 57 |

Notes:

No listings for Marine mammals; Marine fish, sharks and rays; Aquatic invertebrates; and Fungi.

Over the past three years, an additional 18 species (+2%) have been listed, including 17 mainly land-based species (+2%) under the Biodiversity Conservation Act and one aquatic species (+3%) under the Fisheries Management Act.

Table 11.1 shows the number of listings by threat listing category and by plant or animal group. The groups at greatest risk of extinction are:

- land-based mammal species (60% of all species are threatened)

- amphibian species (35%)

- birds (31%).

In addition, 36% of all freshwater fish species in the Murray–Darling Basin are listed as threatened. The relative number of some listed species, such as aquatic plants, invertebrates, fungi and alga; are low compared to other threatened species such as birds, mammals and plants. In part, this is likely an underestimate due to lack of information and low taxonomic resolution about most species.

The 2% increase in threatened species over the three years to the end of 2020 represents a slight decrease in the rate of species listings compared to the previous reporting cycle, but this may not reflect an actual change in the outcomes for species.

Since 2017, the number of species listed as extinct increased by one bird species to 78 – the thick-billed grasswren (Amytornis modestus inexpectatus).

Other changes in the numbers of listings for the period 2018–2020 are:

- an increase in the number of critically endangered species by 16% from 100 to 116

- three more threatened ecological communities taking the total to 115.

Figures 11.1 and 11.2 show the change over time in the number of threatened species and ecological community listings from 1995 to 2020.

Figure 11.1: Changes in total listings of threatened species, 1995–2020

Notes:

Categories used:

Critically endangered: Species and ecological communities are listed as critically endangered if they are facing an extremely high risk of extinction in Australia in the immediate future. Critically endangered was only added to the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 as a listing category in 2007

Endangered: Species or ecological communities are listed as endangered if they face a very high risk of extinction in Australia in the near future, and are not eligible to be listed as a critically endangered species or ecological community.

Vulnerable: Species and ecological communities are listed as vulnerable if they face a high risk of extinction in NSW in the medium-term future, and are not eligible to be listed as an endangered or critically endangered species or ecological community.

Extinct species: Species are listed as extinct if there is no reasonable doubt that the last member of the species in Australia has died. Species that are listed as extinct in the wild are species known to survive in Australia in cultivation, in captivity or naturalised population outside the past range or it hasn't been recorded in its habitat in Australia despite surveys in a time frame appropriate to their life cycle and type.

Figure 11.2: Changes in total listings of NSW ecological communities, 1995–2020

Reliability of threatened species listings

In the absence of other broad-scale data for monitoring changes in species populations, the listing of threatened species has long been used as an indicator to report on outcomes for biodiversity. With more data now available (see the topic), these listings have provided continuity and a stable source of information about the effectiveness of conservation programs in stabilising native plant and animal numbers.

However, changes in species listings, especially trends in the rate of listings over time have proved difficult to interpret and are a matter of ongoing debate (Keith & Burgman 2004). Furthermore, historical inconsistency between state, Commonwealth and international criteria and processes listing threatened species has led to potentially incorrect listing or non-listing of species and misdirected conservation efforts (; ).

These growing criticisms of threatened species listings have also included:

- bias towards conserving iconic species, such as koalas (; )

- over-reliance on public nominations ()

- resourcing constraints on the NSW scientific committees that assess nominations for listing ()

- allocation of resources to scientific committees for specific purposes biasing assessments to these groups

- restrictions on the time, knowledge and skills required to make effective listing nominations.

Most importantly, the changes in totals and rates of listings are not representative of overall outcomes for all species, as the listing process began relatively recently in 1995 and many species have been under threat for much longer.

Biodiversity Indicator Program

The Biodiversity Indicator Program (BIP) aims to monitor the condition of biodiversity and ecological integrity in NSW and how well management and conservation measures are working. Results from the first baseline assessment of biodiversity are available in the Biodiversity Outlook Report and a supplementary assessment is also available following the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20.

BIP indicators assess the likelihood of the long-term survival over 100 years of species and ecological communities listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation Act. They are calculated by summing the probabilities of survival for all listed species or ecological communities according to their listing category (vulnerable, endangered, critically endangered or extinct) and the Criterion E estimates of the probability of extinction for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Future change in the value of the indicator can reflect either a change in the threat category of species due to a decision of the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee or a change in the probability of survival due to effective management of the species.

At August 2017, a total 991 of NSW species were listed as threatened (or extinct) under the Biodiversity Conservation Act. The majority (88%) of listed species belong to well-known groups (plants, birds, mammals etc.).

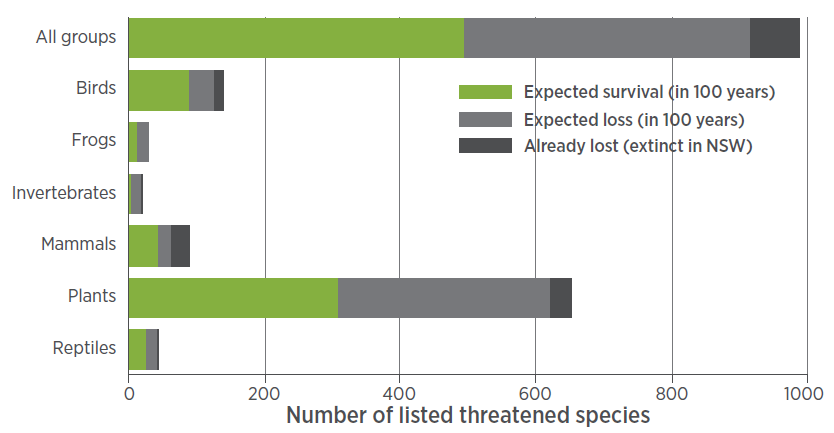

Figure 11.3 shows the number of threatened species predicted to survive or become extinct in 100 years’ time. The BIP methodology predicts that 496 species (50%) are expected to survive in 100 years. Investment in biodiversity conservation may slow, halt or reverse this trend.

Figure 11.3: Number of NSW species listed as threatened expected to survive in 100 years by biological groups and all groups combined

Notes:

Threatened species expected to survive in 100 years from 25 August 2017

At 25 August 2017, a total of 108 ecological communities were also listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation Act. Of these, 64 (59%) are expected to exist in 100 years.

Phylogenetic diversity

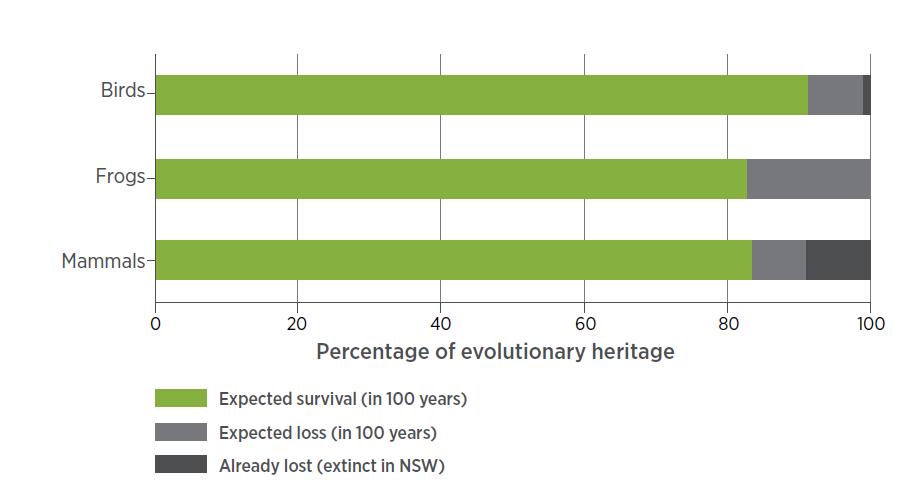

BIP has an indicator for the expected survival in 100 years’ time of the unique evolutionary heritage represented by the species of New South Wales. Because Australian animal species are often very distinctive and found nowhere else, this unique evolutionary heritage is substantial and irreplaceable. Birds, mammals and frogs have evolutionary trees that include all known species and are fully dated. The trees show the evolutionary relationships between species of birds, mammals and frogs and how long ago any pair of species shared a common ancestor.

‘Phylogenetic diversity’ measures evolutionary heritage as the sum of all lengths of the branches in an evolutionary tree which connects all the species in the tree via their common ancestors. The BIP indicator estimates what proportion of the evolutionary tree (phylogenetic diversity) is expected to be extant in 100 years from the probability of survival of each evolutionary branch. A branch of the tree will survive if at least one of the species that descended from that branch survives. Figure 11.4 displays the phylogenetic diversity that is expected to survive for different groups in 100 years’ time from assessments made in 2017. Birds, frogs and mammals are expected to retain 92%, 83% and 84%, respectively, of their original evolutionary heritage in 100 years.

Figure 11.4: Evolutionary diversity (as a percentage of an evolutionary tree) from different biological groups expected to survive in 100 years

Notes:

Based on listings as at 25 August 2017

Saving our Species outcomes

Without management, the trend for threatened species and other listed entities is poor as the threatened species list grows and many threats show no sign of abating. The Saving our Species (SoS) program is committed to securing in the wild the maximum number of threatened species and ecological communities for the next 100 years.

The amount of information about threatened species outcomes has steadily increased since the program began. The two main SoS indicators used by the program to track progress in securing the state’s threatened biodiversity are the:

- number of threatened species and ecological communities under effective management

- number of threatened species and ecological communities on track to be secure in the wild.

Threatened species and ecological communities effectively managed

The first SoS indicator gauges the number of threatened species and communities being actively managed in accordance with the program’s specific conservation strategy and associated management stream objectives. SoS also tracks the number of projects investing in managing key threatening processes.

The number of entities under management has steadily increased from the 297 in 2016–1 (see Figure 11.5). By 2018–19, there were 465 active projects, for roughly 40% of the listed species, communities and populations in NSW.

Figure 11.5: Number of entities and processes under active management in the Saving our Species program, 2016–17 to 2019–20

The number fell slightly in 2019–20, when bushfires caused the program to concentrate on emergency response for existing projects and complete 40 survey/research-focused projects on changed circumstances. Some of these species were found not to require active intervention once sufficient data was collected.

Current research partnerships between DPIE’s Saving our Species and the CSIRO indicate that more species could benefit from the actions currently being taken on the ground, with only minimal additional investment.

Threatened species and ecological communities on track to security in the wild

The second SoS indicator assesses the number of species and communities with sufficient management to be considered on track to long-term security in the wild.

Species are determined to be ‘on track’ to be secure in the wild in 100 years if monitoring indicates the population measure has met its annual target. Where monitoring results are not available for a species, but indirect indicators, such as threat monitoring or management actions have met annual targets, an outcome is ‘inferred on track’. If a species response is not detectable and intermediate indicators are not met, an ‘inferred not on track’ would be applied. Species are ‘not on track’ if monitoring indicates the population measure does not meet the annual target.

Species Recovery Index

To assess species recovery outcomes, a previously published method for developing a recovery index was used (). Based on SoS annual reporting outcomes for iconic and site-managed species, a four-year recovery index was calculated for species with complete data between 2016 and 2020. Data availability varies by species due to how often the species is monitored.

A total of 203 species met this criterion (four iconic and 199 site-managed.) Each year was scored individually for each project, depending on whether the species meet its target range. The possible outcomes were ‘on track’ (scored as +1), ‘inferred on track’ (+1), ‘inferred not on track’ (0) and ‘not on track’ (–1). These scores were then summed for each project across the four years.

If a species project scored a total of +4, the index of recovery suggests it has met its target every year for four years. By comparison, a score of –4 would indicate project outcome indicators have fallen below the target range over consecutive years.

The recovery index (see Figure 11.6) shows that the majority of SoS projects in this group (95 species or 42%) had positive population outcomes over consecutive years. For the 89 species (40%) with a recovery index between 1 and 3, responses were variable but overall demonstrated a positive response to intervention. An additional 36 species (16%) had recovery index scores between 0 and –3, showing little response to management intervention or a response not yet detected in the four-year timeframe. Only four species (2%) showed a net negative response to management intervention and consistently fell below the target.

Figure 11.6: Saving our Species Recovery Index – 2016–17 to 2019–20

Notes:

The recovery index is the sum of annual reports in which the species is ‘On track’ (+1), ‘Inferred on track’ (+1), ‘Inferred not on track’ (0) and ‘Not on track’ (–1) for the first four years of the program (2016–17 to 2019–20).

Pressures

Listing of key threatening processes

The biodiversity of NSW is subject to an increasing number and range of threats. The Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the Fisheries Management Act 1994 both list the key threatening processes (KTPs) that impact on listed threatened species.

At 31 December 2020, a total of 47 KTPs were listed for NSW – 39 under the Biodiversity Conservation Act and eight under the Fisheries Management Act. There is some overlap in the threat listings, with climate change, shark meshing and changes to river flow regimes listed under both Acts in slightly different forms.

Table 11.3 summarises the types of KTPs listed. Over half relate to invasive species, with 25 associated with pests and weeds and a further five pertaining to pathogens and diseases. Ten KTPs relate to the clearing and disturbance of native habitat.

One additional KTP has been listed over the latest reporting period: Habitat degradation and loss by feral horses (Equus caballus) Linnaeus 1758.

Table 11.3: Key threatening processes listed in NSW, 2020

| Issue | Number of KTPs |

|---|---|

| Invasive species | 25 |

| Habitat change | 10 |

| Disease | 5 |

| Over-exploitation | 3 |

| Climate change | 2 |

| Altered fire regimes | 1 |

| Pollution | 1 |

| Total | 47 |

Notes:

As at 31 December 2020.

It should be noted that not all of these threats are equivalent in effect and the numbers are not necessarily indicative of the cumulative impact of any type of threat. For example, it is expected that over time climate change will become one of the most significant of all the threats described here.

Main threats to biodiversity and threatened species

When a species, population or ecological community is listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation or Fisheries Management Act, the main pressures and threats affecting its conservation status are described in the listing. These threats were analysed for all threatened species listed at the time of analysis under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, the predecessor to the current Biodiversity Conservation Act, to identify those that have the greatest impact on biodiversity and the environment in NSW ().

The pressures affecting the largest number of threatened species in NSW were found to be native vegetation clearing and permanent habitat losses (87%), followed by invasive pest and weed species (70%).

Permanent clearing and habitat destruction

The clearing of native vegetation results in the direct loss of species and destruction of habitat, followed by lag effects due to disturbance from subsequent land uses and the fragmentation of remnant vegetation. This in turn impedes regeneration and the movement of species across the landscape, leading to a loss of genetic diversity (; ).

The decline in habitat condition through clearing and fragmentation is described by three Biodiversity Indicator Program indicators for habitat quality – ecological condition, ecological connectivity and ecological carrying capacity. The baseline level of ecological carrying capacity remaining in 2013 was assessed at 33% of the natural levels before European settlement and 31% in 2020 following the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. These indicators are discussed further in the Native vegetation topic and the Biodiversity Outlook Report.

The Land Management and Biodiversity Conservation reforms commenced in August 2017 and changed how native vegetation is managed across rural regulated land in NSW. The rate of permanent native vegetation clearing has significantly increased since this time (see Native Vegetation Topic). A Rural Boundary Clearing Code was also introduced in September 2021, giving landholders an option to clear certain vegetation within 25 metres of their landholding’s boundary to reduce potential bushfire spread. This may further change the rural vegetation landscape.

Invasive species

Invasive species have contributed to the decline of many native species. Pest animals, particularly foxes and cats, are likely to have had the greatest impact on native fauna and are considered to be responsible for the majority of mammal extinctions on mainland NSW (; ; ). Black rats had a similar effect on endemic bird species on Lord Howe Island, while introduced carp is now the predominant species in most rivers of the Murray–Darling Basin.

Climate change

As many Australian species are adapted to highly variable climates, they are likely to have the capacity to cope with a certain level of climate change. However, the resilience of many species has been eroded by other existing pressures, resulting in the declines in numbers and range described in this and the Native fauna topic. Climate change is expected to exacerbate the effects of existing threats and introduce additional pressures (; ; ). Climate change is likely to surpass habitat destruction as the greatest global threat to biodiversity over coming decades (). For further information see the topic.

Other threats

Water extraction and altered river flows and cycles affect the critical ecological processes that trigger breeding in a range of aquatic and bird species (see the River health topic), while altered fire regimes impact the ability of plant species and communities to regenerate or repropagate.

Most of the main threats to biodiversity in NSW are described in greater detail in other sections of this report, including:

- clearing, fragmentation and the disturbance of native vegetation (see )

- the introduction and spread of invasive species – pests, weeds, diseases and pathogens (see )

- lack of groundcover retention (see )

- water extraction and changes to river flows (see )

- increasing populations and expanding human settlements (see )

- the increasing impacts of climate change (see )

- altered fire regimes due to European settlement and climate change (see ).

Threats not dealt with specifically in other sections of this report include:

- the indirect impacts of development, particularly in new areas where high rates of mortality and injury to wildlife can occur

- disturbance to behaviour and breeding cycles from infrastructure, noise and lighting ().

It should be noted that many of these threats can operate together to have a cumulative impact and hasten the decline of species and communities. Sometimes these impacts may be synergistic, where the cumulative impact is greater than the sum of the individual pressures (; ; ).

Lack of information

It is unrealistic to expect that a full range of biodiversity could ever be monitored systematically with the resources available. Compared to plants and mammals, there is much to learn of the taxonomy of insects, fungi, and algae. Much of this taxonomic work is done by museum and herbarium-based taxonomists and generally underfunded. The ongoing challenge, therefore, is to optimise the collection of the information necessary to manage biodiversity as effectively as possible.

Although knowledge of the conservation status of species has improved markedly over the past 20 years, especially the distribution and abundance of land-based vertebrates, less is known about other groups. Patterns of decline that are likely to have been present for many years are still being discovered in the less well-studied groups of species. For most invertebrates, microorganisms and many plant groups which comprise the vast majority of species, information exists for only a few isolated species and this provides little insight into the broader status and management needs of these groups.

The 2014 Independent Biodiversity Legislation Review panel recommended the development of a comprehensive system for monitoring and reporting on the extent and quality of biodiversity in NSW (). In response, the Biodiversity Indicator Program was established in 2017 to collect, monitor and assess information on the status and trends in biodiversity in NSW. The results of the first NSW Biodiversity Outlook Report were published in February 2020 and are summarised above in this topic and the Native vegetation topic. A Forest Monitoring and Improvement Program (FMIP) established and overseen by the Natural Resources Commission has been established as part of the Regional Forest Agreement renewal process.

Responses

Legislation and policies

Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016

Following the Independent Biodiversity Legislation Review, sweeping reforms were made to the legislative framework for land management and biodiversity conservation, taking effect from August 2017. Biodiversity legislation in NSW was consolidated under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, which replaced the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001 and the plant and animal provisions of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. A new rural land management framework was also introduced with the Local Land Services Amendment Act 2016. The framework for regulating impacts on native vegetation from rural land management activities applies a risk-based approach to authorising clearing (see Native Vegetation topic for more information). This replaced the Native Vegetation Act 2003, which, as one of its objectives, was put in place to prevent broadscale clearing except where it improved or maintained environmental outcomes.

Protections for aquatic and marine species remain in the Fisheries Management Act 1994. Amendments to the Act are still being progressed to make this legislation consistent with the Biodiversity Conservation Act and the Common Assessment Method for national listing of threatened species.

Policy and guidelines for fish habitat conservation and management

In 2013, an updated policy and guidelines were published to maintain and enhance the habitat of native fish species (including threatened species) in the marine, estuarine and freshwater environments (DPI 2013).

Programs

Saving our Species

Saving our Species (SoS) is a ground-breaking statewide conservation program that addresses a number of plants and animals in NSW facing extinction. The objectives of SoS are to:

- increase the number of threatened species that are secure in the wild for the next 100 years

- control the key threats facing our threatened plants and animals.

The program is driven by a framework that:

- uses a science-based approach to plan and prioritise the actions needed to conserve each species in the wild for the next 100 years by producing practical management strategies for each site

- provides increased opportunities to work with partners in the community, including the private sector and Aboriginal people, to deliver effective work on the ground

- drives evaluation and transparent public reporting through rigorous monitoring and evaluation that ensures threatened species recovery is driven by the best available science.

Under Saving our Species, every threatened species project falls into one of nine management streams that groups together species based on their ecology and management requirements. Each management stream has a specific objective, performance indicators and a monitoring approach to ensure achievement of outcomes.

The nine management streams are as follows:

- Site-managed species are those for which discrete populations can be geographically defined and critical threats identified and feasibly managed and where mitigation of these threats at a selection of sites is likely to secure the species in NSW in the long term.

- Landscape species are typically widely distributed, highly mobile or dispersed, and best recovered by managing threats associated with habitat loss or degradation at a landscape scale.

- Iconic species: Species in the iconic stream are important to the community socially, culturally and economically and there are high expectations for their effective ecological management. Iconic species, are able to leverage support for SoS from the wider community, through their role as flagship species for the program.

- Partnership species are animals and plants listed as threatened in NSW that have less than 10% of their total distribution in the state. As partnership species occur across state or territory borders, the best way to conserve them is to work with other jurisdictions.

- Data-deficient species: Species are allocated to the data-deficient management stream when there is insufficient knowledge about their ecology, distribution, threats or management needs to inform an effective management strategy. Typically, data-deficient species need investment in targeted research or surveys to fill these knowledge gaps and determine the best approach to on-ground management.

- Keep watch species: The SoS program allocates species to this stream where strong quantitative evidence shows the species populations are secure without targeted investment in management. Strategies for keep watch species include monitoring actions only to ensure populations remain stable or improve and identify potential new and/or emerging threats to the security of the species.

- Threatened ecological communities: An ecological community is a naturally occurring collection of native plants, animals and other organisms occupying a particular area. Where ecological communities are threatened, SoS works to guide stakeholder investment in broad-scale reserve planning, restoration, revegetation, increasing habitat connectivity, private land stewardship and land management, as well as more targeted on-ground activities.

- Key threatening processes are a focal point for SoS as they drive the extinction of species and ecological communities. Some of the most destructive key threatening processes (KTPs) in NSW are pests and weeds, climate change and habitat loss. In managing KTPs, threat abatement is fundamental to ensuring the long-term viability of threatened species and ecological communities.

- Threatened populations: A threatened population is a group of plants or animals of the same species occupying a particular area that is listed in the legislation as likely to become extinct in the near future. Because threatened populations are geographically discrete, critical threats can be managed at priority sites to secure a threatened population in the long term.

For each listed species, ecological community and key threatening process, Saving our Species develops a conservation strategy that lists the critical sites, threats and actions needed to secure a species in the wild. These strategies guide the work on the ground to manage and restore the 369 species, 15 key threatening processes and 40 threatened ecological communities covered by the program.

SoS outcomes are discussed in the Status and trends section of this topic.

In June 2021, the NSW Government announced a further $75 million of funding over the next five years (2021–2026) for the Saving our Species program. This brings the total investment in the program to $175 million over the ten years to 2026.

Reintroduction of locally extinct mammals

Since 2016, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service has been working with the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) and the University of New South Wales (Wild Deserts) to reintroduce up to 13 locally extinct mammal species into three national park reserves. The NSW Government has committed $41.3 million over 10 years towards this feral-predator free area partnership project, part of the Saving our Species program.

As part of this project, fenced areas have already been established at Sturt National Park, Mallee Cliffs National Park and the Pilliga State Conservation Area. As of December 2021, feral-free fences are protecting just under 20,000 hectares and eight mammal species have been reintroduced.

On 18 December 2020, the NSW Government announced the establishment of four new feral predator-free areas.

The extended project proposes one of the most significant threatened fauna restoration projects in NSW history, enabling the reintroduction of 28 locally extinct species (23 of them threatened) and delivering a measurable conservation benefit for at least another 30 threatened species which, in turn, will help restore essential ecosystem function and processes (see topic).

Wildlife licensing

The Biodiversity Conservation Act established a risk-based approach to managing wildlife actions through a tiered framework that:

- permits low-risk activities through Biodiversity Conservation Regulations

- allows moderate risk activities under a code of practice

- ensures high-risk activities will continue to require a licence

- provides for actions that have direct impacts on biodiversity, including threatened species, to be treated as offences under the Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Although currently underutilised, wildlife licensing data from surveys, rescued and rehabilitated wildlife records, and keeping of wildlife, has the potential to supply useful information on locations and threats for threatened species ().

The NSW Government is consulting with stakeholders to identify which actions should continue to require licensing and which should be regulated by codes of practice and regulations.

Identifying areas of outstanding biodiversity value

The Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 enables the Minister for the Environment to declare Areas of Outstanding Biodiversity Value (AOBVs). These are special areas that contain irreplaceable biodiversity values that are important to the whole of NSW, Australia or globally. The purpose of declaring an AOBV is to identify, highlight and effectively conserve areas that make significant contributions to the persistence of biodiversity. See topic.

Existing areas of declared critical habitat under the repealed Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, including Little Penguin and Wollemi Pine declared areas, became AOBVs when the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 came into effect.

Listing of threatened species and communities

The Biodiversity Conservation Act modernised the process for listing threatened plants and animals. It aligns threat categories with international best practice and provides greater coordination between Australian jurisdictions. The Biodiversity Conservation Regulations prescribe criteria for listing threatened plants and animals which align with standards developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Commonwealth, state and territory governments agreed to establish a common method for assessing and listing threatened species. In NSW, the Threatened Species Scientific Committee, established under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, is an independent committee of scientists appointed by the Minister for the Environment to consider the listing of threatened species and communities. For example the Committee assesses the risk of extinction of a species in Australia and determines which species should be listed as critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable or extinct in NSW.

The process of aligning assessment and listing under a common method is ongoing. It will reduce duplication of effort among governments by allowing jurisdictions to adopt successful listing assessments by other jurisdictions and lead to better conservation outcomes for Australia's species.

NSW public reserves system

The public reserves system is the cornerstone of conservation efforts in NSW. It plays a vital role in protecting habitat and provides a refuge for many threatened species that are sensitive to habitat disturbance.

The NSW public reserves system covers around 7.56 million hectares or about 9.4% of the state (see the topic). It conserves representative areas of most habitats and ecosystems and the majority of NSW plant and animal species are found in the public reserve system. The Biodiversity Conservation Act adopted an increased focus on conservation measures on private land to supplement land managed for conservation in the public reserve system.

NSW Koala Strategy

The NSW Government recognises the koala as an iconic threatened species and is committed to stabilising and increasing its populations across NSW. In May 2018, the government released the NSW Koala Strategy, supporting a range of conservation actions over three years. The strategy was a response to the Independent Review into the Decline of Koala Populations in Key Areas of NSW (), which recommended a whole-of-government koala strategy for NSW. An expert advisory committee chaired by the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer guided the strategy’s development along with extensive community and stakeholder consultation.

In June 2021, the NSW Government announced the investment of $193 million over 5 years into koala conservation, to assist to meet its target of doubling the NSW koala population by 2050. Through this new program, conservation actions to increase koala numbers will be delivered under four pillars of conservation: conserving koala habitat, supporting local communities to conserve koalas, improving the safety and health of koalas, and building our knowledge to improve koala conservation.

Management and control of invasive species

Once established, the eradication of invasive species is seldom feasible. Therefore, control of some high-priority invasive species, such as foxes and bitou bush, is specifically targeted at sites of high conservation value. Control is delivered through threat abatement plans which facilitate whole-of-government coordination across agencies and local authorities.

Broad-scale rabbit control is being provided through the release of rabbit haemorrhagic disease. Local Land Services is responsible for identifying priority weeds regionally and developing programs to manage them (see the topic).

The use of the predator-proof fences used for the reintroduction programs can also be listed as a control for the impacts of invasive species.

Adaptation to climate change

Priorities for Biodiversity Adaptation to Climate Change () was produced in response to the listing of anthropogenic climate change as a key threatening process under the Biodiversity Conservation Act. This identifies priority measures for dealing with the effects of climate change, focusing on four key areas:

- enhancing understanding of the likely responses of biodiversity to climate change and readjusting management programs where necessary

- protecting a diverse range of habitats by building a comprehensive, adequate and representative public reserve system in NSW, with a focus on under-represented bioregions

- increasing opportunities for species to move across the landscape by working with partners and the community to protect habitat and increase connectivity by consolidating areas of vegetation in good condition

- assessing adaptation options for ecosystems most at risk from climate change in NSW.

A key threatening processes strategy has been prepared for the SoS program, that includes adaptation processes in response to climate change following the listing of Climate change as a KTP.

The AdaptNSW website provides comprehensive climate change information, analysis and data to support action to address climate change risks and capture opportunities. It includes information on the causes of climate change and the likely impacts on biodiversity. For further information see the topic.

Future opportunities

Conservation of threatened species outside the reserve system is a field of growing importance. Measures to improve connectivity across landscapes and build the health and resilience of the land will enhance the capacity of species and ecosystems to adapt to, and cope with, disturbance.

More information about the factors contributing to the resilience or success of some native species and processes, in contrast to the declines of many others, may assist in efforts to maintain sustainable populations of flora and fauna species.

The NSW Government will conduct a statutory five-year review of the land management and biodiversity conservation framework commencing in 2022. This will be an opportunity to assess impacts of recent legislative change on threatened species and their native vegetation habitats, and assist in planning future responses and safeguards to protect threatened species and ecological communities.

Monitoring of the impacts of population and survival of threatened species after management actions, particularly funded through Saving Our Species, would provide much needed information on how to best conserve species.

There is scope to introduce significant qualitative data on Aboriginal cultural species to understand how significant cultural species are faring and ways to care for them and their habitats. Qualitative data collection includes oral stories and knowledge about Aboriginal culture and practises. The EPA Aboriginal Knowledge Group notes the need for management authorities to learn more and apply how Aboriginal cultures and practices improve the care, protection and management of species, their habitats and the overall environment. It recommends that support for this remerging research and understanding is essential for all aspects of environmental health

References

Cogger H, Dickman C & Ford H 2007, The Impacts of the Approved Clearing of Native Vegetation on Australian Wildlife in New South Wales, WWF-Australia, Sydney

Keith DA & Burgman MA 2004, ‘The Lazarus effect: Can the dynamics of extinct species lists tell us anything about the status of biodiversity?’, Biological Conservation, 117, pp. 41–8

Morton SR 1990, ‘The impact of European settlement on the vertebrate animals of arid Australia: A conceptual model’, in Saunders DA, Hopkins AJM & How RA, Australian Ecosystems: 200 years of utilisation, degradation and reconstruction, Proceedings of a symposium held in Geraldton, Western Australia, 28 August–2 September 1988, Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia, 16, pp. 201–13

Raffaele EA, Veblen TTB, Blackhall MA & Tercero-Bucardo NA 2011, ‘Synergistic influences of introduced herbivores and fire on vegetation change in northern Patagonia, Argentina’, Journal of Vegetation Science, 22(1), pp. 59–71

Simberloff D & Von Holle B 1999, ‘Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: Invasional meltdown?’, Biological Invasions, 1(1), pp. 21–32

Taylor MFJ & Dickman CR 2014, NSW Native Vegetation Act Saves Australian Wildlife, WWF-Australia, Sydney