Summary

Invasive species have been in NSW for a long time. Virtually every part of the state is affected by pests and weeds that threaten native species, ecosystems, agricultural productivity and landscape processes, such as the production of clean water.

Why managing invasive species is important

Australian native plants and animals have co-evolved over millions of years. As a result, the introduction of non-native pests and weeds can seriously threaten native species because native species have not evolved ways to deal with them. Invasive species are implicated in the decline of land and aquatic species and the extinction of many small Australian native mammals and birds.

For example, weeds such as lantana can drive out native flora species and change the population of ecosystems. Invasive animals such as feral cats can prey on threatened animals, drastically reducing their numbers. Pests and weeds can also impact on agricultural productivity, social wellbeing and ecotourism ().

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of new invasive species detected |

|

Stable | ✔✔ |

| Spread of emerging invasive species |

|

Getting worse | ✔ |

| Impact of widespread invasive species |

|

Stable | ✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are defined in .

Status and Trends

The extinction or decline of numerous small- to medium-sized animals, particularly mammals, has largely been attributed to predation by foxes and cats, while rats introduced to Lord Howe Island caused nine of the 14 bird extinctions in NSW.

Grazing and browsing by introduced herbivores, such as rabbits, goats and deer, has led to habitat degradation and a decline in native vegetation diversity and productivity. Pest fish threaten native fish species and aquatic ecosystems, with carp dominating fish community biomass across most of the Murray–Darling Basin.

Spotlight figure15 shows species, populations and ecological communities threatened by key terrestrial invasive species.

Spotlight figure 15: Species, populations and ecological communities* threatened by key terrestrial invasive species**

Notes:

* Threatened species, populations and ecological communities listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016

** The invasive species selected are generally those listed as key threatening processes.

Data compiled by aggregating the threats affecting each threatened species, identified at the time of listing, across all threatened species.

Considered individually, widespread pest animals, such as feral cats and foxes, have a far greater impact on threatened species than individual weed species. However, the overall number of weed species is much greater than pest animal species and their combined impact is broader than the impact of pest animals.

Pressures

Pest animals and weeds continue to spread, adding to other pressures on the natural environment such as addition of nutrients, changed hydrologic regimes, bushfires and climate change.

Invasive pathogens, particularly the root rot fungus (Phytophthora), myrtle rust and the amphibian chytrid fungus, are increasing threats to biodiversity.

New invasive species are being introduced by the black market pet trade, nursery industry and aquarium industry or as stowaways on boats. These newly introduced and emerging invasive species can have an impact on additional threatened flora and fauna, and potentially add to the cumulative impact of all invasive species on the environment.

Responses

The NSW Invasive Species Plan 2018–2021 () sets out the priorities, goals, strategies and guidelines to exclude, eradicate or manage invasive species and their impacts. The NSW Biosecurity Strategy 2013–2021 () manages shared responsibility for effective biosecurity management, increases awareness of biosecurity issues in NSW and outlines ways in which the NSW Government works in partnership with other government agencies, industry and the community to manage biosecurity risks.

Response programs are important in mitigating the threats from invasive species. They include:

- the State Weed Committee which is responsible for ensuring a coordinated and strategic approach to weed management in NSW

- Regional Weed and Pest Animal Committees which coordinate regional pest and weed management activities

- Saving our Species which manages projects to protect threatened species from pests and weeds

- the National Carp Control Plan which helps manage carp populations.

Other initiatives include:

- improvements to surveillance and biosecurity measures to help prevent new invasive species threats

- a better understanding of pathogens which continue to emerge as an increasing threat

- schemes such as aerial baiting which have been successful in controlling foxes in some areas and may even help control feral cats.

Related topics: | | |

Context

Australian native plants and animals have co-evolved over millions of years. The introduction of non-native invasive species can seriously threaten native species because they have not evolved ways to deal with them. Invasive species are implicated in the decline and extinction of many Australian native plants and animals in both land-based and water-based ecosystems. See the , and topics for more information.

Invasive species harm native species and the natural environment in NSW by:

- preying on or infecting them

- competing with them for resources

- modifying and degrading habitats

- transmitting disease

- reducing native biodiversity

- disrupting ecosystem processes.

Introduced marine species can threaten marine environments and the animals, industries and communities they support. Freshwater fish, such as carp and tilapia, out-compete and predate on native species, disrupt ecosystems and reduce water quality and native biodiversity.

Many of the state’s invasive pest animals and weeds were introduced intentionally before it was realised how damaging they could be to native species and livelihoods. Examples of introduced pests include:

- pigs and goats

- pets, such as cats

- foxes and deer for hunting

- plants for economic purposes, such as crops or bitou bush for erosion control

- escaped garden plants

- animals for controlling other pests, such as Eastern gambusia fish introduced in the early 20th century to control mosquitos.

More recently, invasive species have been inadvertently introduced into NSW in vehicles, equipment, packing material and soil or garden refuse or by ocean shipping. An example would be weeds such as parthenium being inadvertently introduced in imported feed. Emerging threats include:

- amphibians, such as black spiny toads

- introduced turtles, such as red-eared slider turtles

- insects, such as red imported fire ants and yellow crazy ants.

In this report, estimated costs to the economy do not include environmental and social impacts but do include the costs of control in environmental areas.

Status and Trends

Categories of invasive species

‘Invasive species’ is a general term that describes pest animals, weeds and other organisms, such as pathogens, that are introduced to places outside their native ranges, where they spread and negatively affect local ecosystems and species ().

Invasive species are generally categorised as widespread, emerging or new, depending on the extent to which they have become established and spread:

- Widespread species are invasive species that have been present for a substantial period of time, during which they have established a broad range across a region or statewide with further significant expansion unlikely.

- Emerging species are invasive species that have established self-sustaining populations that are expanding their range or have the potential for significant further spread.

- New species are those that have not been recorded in NSW or are not yet established self-sustaining populations, but that could invade and spread.

Environmental impacts of invasive species

Extinctions

The main factor identified in the majority of animal extinctions in NSW is predation by foxes and cats. Extinct species have generally been small to medium ground-dwelling mammals, such as small wallabies, native mice, bandicoots and bettongs (). Many of them inhabited arid shrublands and grasslands in the west of the state and most had become extinct by the end of the 19th century.

Rats were introduced to Lord Howe Island when a cargo ship ran aground in 1918. They subsequently became the main cause of an extinction hotspot, responsible for the loss of nine of the 14 bird species that are extinct in NSW, all of them endemic to Lord Howe.

Impacts on threatened species

Collectively, weeds and pest animals have been identified as a threat to approximately 70% of the threatened species listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Invasion by exotic species affects the second-highest number of threatened species, after land clearing (). Recent nation-wide estimates for this issue found that this threat could be as high as 82% ().

The extent of the threat posed by key pest animals and weeds to terrestrial threatened species is illustrated in the Spotlight figure 15 in the topic Summary.

Considered individually widespread pest animals, such as feral cats and foxes, have a far greater impact on threatened species than individual weed species (see Spotlight figure 15). However, the overall number of weed species is much greater than pest animal species and their combined impact is broader than the impact of pest animals. Weeds have a negative impact on 45% of threatened species, populations and ecological communities in NSW, whereas pest animals directly threaten 40% of listed entities (; ).

Listing of invasive species as key threatening processes

The magnitude of the impacts of pest and weed species is reflected in the listing of many invasive species as key threatening processes (KTPs) under both state and federal legislation. Twenty-five of the 47 KTPs listed in NSW under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the Fisheries Management Act 1994 relate to the impacts of weed and pest animal species and a further four to pathogens.

Pest animals listed as KTPs include foxes, feral cats, rabbits, feral pigs, feral goats, ship rats, deer, cane toads, mosquito fish and four invertebrates (feral honeybees, fire ants, yellow crazy ants and large earth bumblebees).

Weed species listed as KTPs include lantana, bitou bush, Scotch broom and African olives, while ‘vines and scramblers’ are listed collectively, as are ‘exotic perennial grasses’ and ‘escaped garden plants’.

Broader environmental impacts

The total impact of introduced species on biodiversity and the environment as a whole is difficult to quantify. Most of the information available about the broad impacts of invasive species is specifically about their impacts on threatened species, not on all flora and fauna () and generally does not describe the intensity or magnitude of the impacts.

While largely unquantified, the broader collective impacts of invasive species on the environment and ecosystem health are substantial. These impacts include soil degradation, landscape and habitat disturbance, structural change and decline in vegetation condition, and changes to watercourses and water quality.

Economic costs

Most recent available data suggests that in NSW, weeds account for $1.8 billion a year in lost production (), while the annual economic loss to the economy from the impact of pest animals is estimated to be more than $170 million (). This includes the cost of management actions.

Extent of invasive species

Since 1788, over 3,000 introduced plants have established populations in Australia (; ). More than 1,750 of these have been recorded in NSW, with over 340 recognised as threats to native biodiversity (). Weeds have been estimated to account for 21% of the total vegetation of NSW ().

Over the same period, more than 650 species of land-based animals have been introduced to Australia. In NSW, 64 species have established wild populations, both terrestrial and freshwater (). Although a smaller number of these are considered invasive, the annual economic loss to the NSW economy from the impact of pest animals in NSW is estimated to be more than $170 million, including the cost of management actions ().

Introduced fish species make up around 25% of freshwater fish species in the Murray–Darling Basin ().

It is not known how many insects and other invertebrates have been introduced into Australia in general and NSW specifically ().

Widespread invasive species

Pest animals

Table 15.1 lists the top five widespread land-based pest animals that threaten native plants and animals (). All are listed in the Biodiversity Conservation Act as key threats to NSW threatened species. Because total removal of established invasive species is rarely feasible, these animals continue to maintain pressure on native species and ecosystems.

Table 15.1: Top five land-based pest animal threats to native animals and plants in NSW, ranked by the number of threatened species affected

| Common name | Scientific name |

|---|---|

| Feral cat | Felis catus |

| Red fox | Vulpes vulpes |

| Feral goat | Capra hircus |

| Rabbit | Oryctolagus cuniculus |

| Feral pig | Sus scrofa |

Other widespread pest species include animals introduced to NSW as domestic livestock following European settlement.

Foxes

Foxes are widespread across all of NSW. Since their introduction, foxes have contributed to severe declines and extinctions of many native fauna species, particularly small- to medium-sized ground-dwelling and semi-arboreal mammals, ground-nesting birds and freshwater turtles. Recent experimental studies have shown that predation by foxes continues to threaten remnant populations of many of these species.

Following the 2019–20 bushfires, fox control was identified as a priority action to protect threatened species. The intensity and scale of the bushfires had severe impacts on forested ecosystems, including reducing the cover available to protect native species from introduced predators. In response, aerial baiting of foxes with 1080 was increased across NSW.

Sodium fluoroacetate (‘1080’) is a naturally occurring chemical that is highly soluble and biodegradable which breaks down in soil and carcasses. 1080 is found in over 30 Australian native plants and therefore many native species have a high tolerance to it. However, introduced pest animals, such as foxes, have a very low tolerance for 1080, allowing baiting programs to selectively target pest animals using very low doses of the chemical ()

Previously, aerial baiting could only be delivered by helicopter. However, trials from 2019 showed that improvements in technology and techniques could allow for very accurate aerial baiting using fixed-wing aircraft, which are more cost-effective than helicopters. This, combined with increased funding, has allowed for a six-fold increase in levels of aerial baiting.

Ongoing research has shown that aerial baiting can remove more than 90% of foxes from the landscape (). Also under investigation is what impact aerial fox baiting has on feral cats. This may allow aerial baiting to be used as part of an integrated approach to also manage feral cats.

Weeds

All parts of NSW are affected by weeds that threaten native animals, plants and ecosystems. The extent and diversity of weed species is highest near the coast, particularly around major towns and cities, and in regions with high rainfall (6). The number of weeds recorded tends to decline from east to west ().

Table 15.2 lists the top 20 widespread weeds that have the most significant impacts on native plants and animals in NSW (). It also shows whether they are listed as a Weed of National Significance and/or a key threatening process under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Table 15.2: Top 20 widespread weeds posing a threat to native animals and plants in NSW

| Common name | Scientific name | Weed of national significance | Key threatening process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madeira vine | Anredera cordifolia | Yes | Yes** |

| Lantana | Lantana camara | Yes | Yes*** |

| Bitou bush | Chrysanthemoides monilifera subsp. rotundata | Yes | Yes*** |

| Ground asparagus | Asparagus aethiopicus | Yes | Yes** |

| Blackberry | Rubus fruticosus species aggregate | Yes | Yes* |

| Scotch broom | Cytisus scoparius subsp. scoparius | Yes | Yes*** |

| Japanese honeysuckle | Lonicera japonica | No | Yes* |

| Broad-leaf privet | Ligustrum lucidum | No | Yes* |

| Narrow leaf privet | Ligustrum sinense | No | Yes* |

| Cat’s claw creeper | Dolichandra unguis-cati | Yes | Yes** |

| Salvinia | Salvinia molesta | Yes | Yes* |

| Serrated tussock | Nassella trichotoma | Yes | Yes**** |

| Cape ivy | Delairea odorata | No | Yes** |

| Blue morning glory | Ipomoea indica | No | Yes** |

| Balloon vine | Cardiospermum grandiflorum | No | Yes** |

| Lippia | Phyla canescens | No | Yes* |

| Bridal creeper | Asparagus asparagoides | Yes | Yes** |

| Mickey Mouse plant | Ochna serrulata | No | Yes* |

| Turkey rhubarb | Acetosa sagittata | No | Yes* |

| Sweet vernal grass | Anthoxanthum odoratum | No | Yes**** |

Notes:

*Relates to the invasion by escaped garden plants key threatening process.

**Relates to the invasion by exotic vines and scramblers key threatening process.

***Species listed as a key threatening process in NSW.

****Relates to the invasion by exotic perennial grasses key threatening process.

Invasive aquatic animals

Alien fish compete for food and space with native fish and frogs. They also prey on fish and frog eggs, tadpoles and juvenile fish, fundamentally altering food webs and habitats.

As a result, two key threatening processes (KTPs) have been listed under the Fisheries Management Act: Introduction of fish to waters within a river catchment outside their natural range and Introduction of non-indigenous fish and marine vegetation to the coastal waters of NSW. The Biodiversity Conservation Act also lists Predation by Gambusia holbrooki Girard, 1859 (Plague minnow or mosquito fish) as a KTP.

The latest surveys of freshwater fish species between 2018 and 2020 have found that few sampled sites are free from introduced fish. Most of the sites sampled were in the Murray–Darling Basin, which generally has fewer native fish species than coastal and other inland drainage divisions. Only 8% of sites were free of introduced fish (down from 13% in the previous reporting cycle) and a small number of sites (3%) contained only introduced fish. Averaged across all sites, introduced taxa accounted for 38% of the fish species collected at each site, 39% of total fish abundance and 61% of total fish biomass.

Figure 15.1 provides information on the abundance of individual introduced fish species.

Figure 15.1: Introduced fish recorded at DPI sampling sites

Notes:

Introduced trout in the sample sites includes brown trout and rainbow trout. Data sourced from over 800 sampling sites in the Murray–Darling Basin and northern coastal rivers.

A number of aquarium fish were also present in low numbers including oriental weatherloach, Mozambique tilapia, swordtail, pearl cichlid, platy and White Cloud Mountain minnow. There was no evidence of any new alien fish species becoming established in the freshwater aquatic habitats of NSW during the latest reporting period.

European carp

Carp (Cyprinus carpio) have been in Australia for over 100 years and are now established in most states and territories, except the Northern Territory. Carp are the most widespread, abundant and detrimental pest in NSW freshwater environments. Their impacts are felt environmentally, economically and socially.

Carp are distributed across most of the Murray–Darling Basin and many coastal river systems, particularly in central NSW from the Hunter River in the north to the Shoalhaven River in the south (including the Southern Highlands and Tablelands). Carp dominate many freshwater fish communities in NSW – in some parts of the Murray–Darling Basin they can comprise 80% of the aquatic biomass and exceed 350 kilograms of fish per hectare ().

According to the National Carp Control Plan, the impacts of carp follow from the species’ particular characteristics:

- Carp are ‘ecosystem engineers’ that modify waterways as they suck up mud. They stir up silt and muddy the water, blocking sunlight to aquatic vegetation and impacting plankton, aquatic invertebrates, waterbirds and native fish.

- Carp are ‘water wreckers’ as their feeding activity lowers water quality and increases nutrient levels. They also impact zooplankton, which normally feed on algae. These factors contribute to blue-green algal blooms that affect recreational use of waterways (such as swimming and skiing).

- Carp are ‘resource hogs’ by taking valuable food away from native fish. This particularly impacts smaller native fish species, but also larger species higher up the food chain.

- Carp are ‘trash fish’ by getting in the way of natives. While carp fishing can be fun, most anglers want to catch natives and carp undermine the recreational fishing industry, worth billions of dollars.

New and emerging invasive species

New and emerging pest animals

Red imported fire ants

In November 2014, red imported fire ants were detected in Port Botany, possibly coming from Argentina. Although listed as a key threatening process, this was the first record of the ants in NSW.

The single nest at Port Botany was located and destroyed. Despite further surveillance, no further nests or ants have been located since the initial infestation and the population was declared eradicated in November 2016.

Yellow crazy ants

Invasion by crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) is a threat in NSW. Crazy ants are ranked as among the world’s 100 worst invading pests. They can disrupt crops and displace or kill invertebrates, reptiles, hatchling birds and small mammals. Crazy ants spray formic acid, which burns humans and animals.

Crazy ants have spread across parts of the Northern Territory and have been regularly intercepted at Australian ports since 1988. Approximately 40% of interceptions have been in NSW.

In 2018, the presence of yellow crazy ants was confirmed in Lismore after a report by a member of the public. This was the first NSW sighting in more than 10 years since the ant had been eradicated from Goodwood Island in Clarence River. The NSW Government, with support from the local community and local government, successfully managed this latest incursion and continues its surveillance.

Deer

Six species of feral deer are present in the wild in NSW and populations of five of them (fallow, chital, red, sambar and rusa) are well established. Deer are continuing to expand in their range across NSW and are now found along both sides of the Great Dividing Range as well as significant populations west of the range. Deer distribution has increased from approximately 8% of the state in 2009 to 17% in 2016 and 22% by 2020. The change in distribution from 2016 to 2020 has been mapped.

Cane toads

Cane toads were reported as an emerging species of concern in 2012 with viable populations established on the far north coast of NSW. An isolated population of cane toads was found to be breeding in southern Sydney in 2010 but, following an eradication program led by Sutherland Council, no further toads have been reported in the area since 2015.

The distribution of cane toads in NSW has previously been mapped. The area south of the Clarence River and west of the Summerland Way has been declared a Cane Toad Biosecurity Zone with a target to eradicate cane toads from this area. See the Responses section for further details.

New and emerging weeds

Emerging weed threats are identified in regional plans and prioritised for surveillance and control. Between 2015 and 2020, more than 70,000 surveillance inspections and over 2,600 control responses were conducted to eradicate or contain new incursions of emerging, high-risk weeds, such as Mexican feather grass, Amazon frogbit, kidney-leaf mud plantain, parthenium weed, boneseed and tropical soda apple.

In NSW, 78 weeds are targets for eradication in all or parts of the state. Twenty-eight high-risk species are also listed as ‘prohibited matter’ under the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015. including the two species discussed below.

Orange hawkweed

Originating from Europe, orange hawkweed is in its early stages of invasion in NSW and Victoria but could spread over 27 million hectares of south-east Australia if left unchecked. The weed was first located in Kosciuszko National Park in 2003. Since 2009, a NSW Government eradication program has controlled all known plants and continues to survey large areas of the park and the Monaro region to detect any fresh incursions.

The development of innovative survey techniques has greatly increased rapid detection of hawkweed in remote areas. Remotely piloted aircraft (drones) fitted with high-resolution cameras are used to survey vast areas and images are processed with an algorithm that detects the bright orange hawkweed flowers. Detection dogs are also being used to find hawkweed plants and seedlings missed by drone and human surveys.

To June 2021, over 4,800 hectares of drone surveillance has led to the discovery of four remote orange hawkweed infestations in Kosciuszko National Park, which have been controlled to prevent further spread. This new data is being used to help refine dispersal models, which will enable future surveillance to target areas most likely to be invaded by the weed and greatly improve the ability to detect and control all plants.

Mouse-ear hawkweed

Mouse-ear hawkweed was first recorded in Kosciuszko National Park, in January 2015, where it was invading native alpine vegetation on the Main Range. Since then, only two small infestations of approximately 200 square metres have been discovered and controlled, despite surveillance across more than 350 hectares in the surrounding areas by humans and weed detection dogs.

In the 2020–21 season, just 51 plants were detected in or near known infested areas, despite 203 hectares searched. Surveillance and monitoring will continue to ensure all plants are found and the seedbank is completely eradicated.

New and emerging aquatic pests

Mozambique tilapia

Mozambique tilapia is an internationally recognised pest fish from southern Africa. The species is hardy and tolerant of both fresh and salty water and was a popular ornamental species before being banned in NSW and other Australian jurisdictions. Tilapia has established populations that dominate native fish in parts of Queensland, including catchments that lie directly adjacent to the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB).

In November 2014, a coastal population was detected in northern NSW, which was found to be not feasible to eradicate. Research has suggested tilapia could become widespread if introduced into the MDB () but the species has not yet been detected there. The NSW Government has established targeted local education and advisory programs so MDB communities can identify the fish if it appears and notify their local council.

Red imported slider turtle

This turtle is considered an emerging species in some urban areas around Sydney. It originates from the mid-western states of the USA and north-eastern Mexico. However, non-native populations of wild-living red-eared slider turtles now occur worldwide due to the species being extensively traded as both a pet and a food item. The species is considered an environmental pest outside its natural range because it competes with native turtles for food, nesting areas and basking sites.

Pathogens

Pathogens are a significant and increasing threat to plant and animal biodiversity in NSW which can seriously affect animal and plant production systems and human health.

Four pathogens are listed as key threatening processes under the Biodiversity Conservation Act:

- beak and feather disease, which affects parrot species

- dieback of native plants caused by the root-rot fungus, Phytophthora cinnamomi

- infection of frogs with chytrid fungus, resulting in the disease, chytridiomycosis

- myrtle rust fungi, affecting plants of the family Myrtaceae.

A strain of myrtle rust was first detected in Australia in April 2010 on the NSW Central Coast (). From there, it spread rapidly, reaching bushland in south-east Queensland in January 2011. The full impact of myrtle rust is yet to be realised, but the latest research indicates that highly-susceptible species in NSW, such as Rhodamnia rubescens and Rhodomyrtus psidioides have already declined considerably in response to this pathogen (). Other less widespread species in the family Myrtaceae have no natural resistance and a range that coincides with the predicted hotspots for myrtle rust (; ).

Pressures

Pressures are those factors which increase the cumulative impacts of a threat. Invasive species interact with other pressures, such as habitat disturbance, and make it more challenging for native species to recover.

Factors that worsen the effects of invasive species or increase their distribution

Habitat disturbance

Factors stressing the natural environment, including the addition of nutrients, changed hydrologic regimes and the frequency and severity of altered fire regimes, promote the invasion of introduced species. This, in turn, puts more pressure on native plants, animals and ecosystems ().

Introduction through trade

Greater mobility and the globalisation of international trade are significantly increasing the movement of people and goods across borders. This increases the risk of accidentally introducing pathogens, insects, weeds and other invertebrate pests. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Greater Sydney received more than 38.5 million international visitors, over 500,000 tonnes of air freight and one million shipping containers every year ().

Many new plant species have been introduced to NSW via the nursery trade, with some escaping from gardens to become weeds (). The serious impacts caused by some escaped garden plants has led to them being listed as a key threatening process in NSW and Australia. Of the weeds that threaten endangered species in NSW, 65% were introduced as ornamental plants (). The nursery industry works proactively with government and the community to prevent the distribution of invasive plants, for example through the Plant Sure Scheme, which encourages the use of ornamental garden plants with low invasive risk.

Other pathways for introducing pests and weeds into NSW are the:

- black-market pet trade, which introduces exotic animals, especially reptiles

- aquarium industry, which introduces exotic fish, such as goldfish and tilapia, and aquatic plant species that have been released into the wild and flourish

- ballast water of cargo ships and hull biofouling, which help spread pests into the marine environment.

Expansions of range

Many invasive species have not yet reached the potential limits of their distribution. For example, weed species, such as African olive, alligator weed, cabomba and many exotic vines, occupy only a small part of their potential range.

Some weeds generally regarded as already widespread, such as lantana, bitou bush, blackberry and Coolatai grass, could expand their spread even further without strategic control to contain it.

Emerging pest animal species, such as deer and cane toads, have not yet reached their full potential range. While deer are continuing to expand, the spread of cane toads has been contained.

Climate change

The impact of climate change on weed invasion is becoming clearer in Australia. As climate regimes continue to change, it is likely that new invasive plants will emerge ().

The extent of suitable habitat for invasive species has been modelled and predicted under current and future climate change scenarios:

- The alpine ecoregion in NSW may be particularly vulnerable to future incursions by weeds ().

- Changing climate regimes may create more favourable conditions for weeds in NSW.

- Many native species and ecological communities affected by climate change will become more vulnerable to the threat of pest animals and weeds.

As a result, climate change scenarios and species distribution models will be useful in predicting future breakouts and the spread of invasive plants and devising suitable management strategies.

Other issues affecting biosecurity

The NSW State of Biosecurity Report 2017 () notes other pressures that are likely to affect biosecurity in NSW, including

- the need to maintain the willingness of government, industry and the community to share responsibility for controlling invasive pests and weeds

- population growth combined with urbanisation and land clearing for development, which provides an increasing biosecurity risk, but also opportunities to engage people in surveillance, detection and control

- the need to embrace new technology and strategies to tackle the changing risk profile of biosecurity in NSW.

Responses

Legislation and policy

The NSW Government determines priorities for control of, and resources to manage, invasive species. The highest priorities for protection are threatened species and other entities listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. For cross-tenure impacts, the community can participate through the regional planning process.

All land managers have a duty to prevent, eliminate or minimise the risk of invasive species under the Biosecurity Act 2015, including participating in coordinated regional strategies.

NSW Invasive Species Plan

The NSW Invasive Species Plan 2018–2021 () focuses on the four goals to:

- exclude – prevent the establishment of new invasive species

- eradicate or contain – eliminate or prevent the spread of new invasive species

- effectively manage – reduce the impacts of widespread invasive species

- build capacity – ensure the NSW Government and community can manage invasive species.

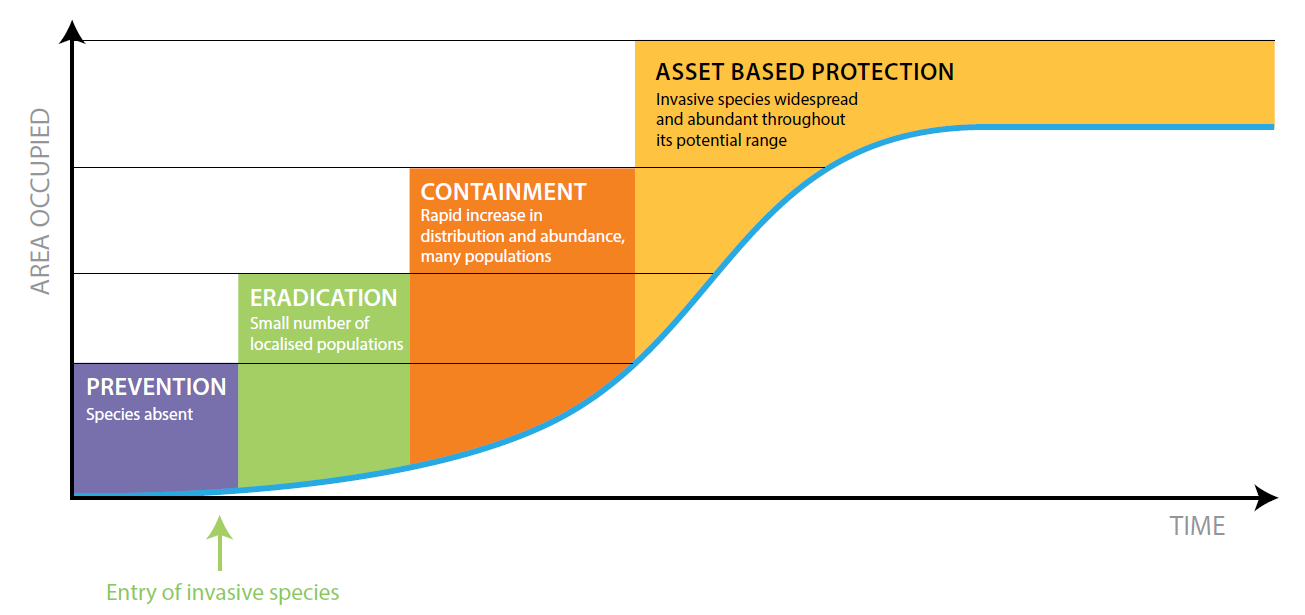

These four goals align with the invasion process from pre-arrival of new invasive species to widespread establishment as illustrated in Figure 15.2.

Figure 15.2: Actions appropriate to each stage of invasive species incursion

Prevention is the most cost-effective way to minimise the impacts of invasive species. Once an invasive species has appeared, it can colonise areas rapidly. Successful control requires a rapid and effective response. Once widespread, the eradication of invasive species over wide areas of different land tenures is rarely practical. Priorities for the control of these species may include focused efforts in areas where the benefits of control will be greatest for the environment, primary production and the community.

The Invasive Species plan:

- dedicates resources to manage invasive species

- identifies key responsibilities for the main parties involved in invasive species management in NSW

- outline critical actions to be taken up to 2021.

NSW Biosecurity Strategy

The NSW Biosecurity Strategy 2013–2021 ():

- explains the principles for sharing responsibility for effective biosecurity management

- increases awareness of biosecurity issues in NSW

- outlines ways in which the NSW Government will partner with other government agencies, industry and the community to identify and manage biosecurity risks.

A key component of the strategy is the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015 and Biosecurity Regulation 2017 which provide for the prevention, elimination, minimisation and management of biosecurity risks.

Another key component of the legislation was the introduction of a ‘General Biosecurity Duty’. This duty requires anyone dealing with a biosecurity matter (such as pest animals or weeds) or a carrier, who knows or should know of the biosecurity risks posed by that matter to take measures to prevent, minimise or eliminate the risk as far as practicable. Occupiers of lands (both private and public) are required to take all practical measures to minimise the risk of any negative impacts of pest animals or weeds on their land. Occupiers can meet their obligations by complying with control actions outlined in Local Land Service Regional Strategic Weed Management Plans and Regional Strategic Pest Animal Management Plans.

NSW authorised officers undertake regular audits and inspections to make sure biosecurity practices are being implemented which helps enable trade. A total of 6,650 compliance and enforcement activities to protect NSW biosecurity were conducted in 2016–17 (). Local Land Services and local authorities also support land holders to meet their biosecurity responsibilities.

Between 2008 and 2017, the NSW Government spent $107 million on significant biosecurity plant and animal disease and pest incident responses.

Land Management (Native Vegetation) Code 2018

The Land Management (Native Vegetation) Code 2018 facilitates native vegetation management on rural land, enabling landowners to productively manage their land while supporting biodiversity and managing environmental risks. The Code allows removal of invasive native plant species on private land that have reached very high densities and dominate an area, making land less productive. Clearing invasive native species may promote the re-establishment of a more desirable mosaic of native vegetation across the agricultural landscape.

Forest Biosecurity Surveillance Strategy

DPI’s Forest Health team are working with Plant Health Australia, the federal and state governments, and other technical experts to develop a National Forest Pest Surveillance Program as part of the . The objectives of the strategy include improving forest pest surveillance coordination, capacity and capability across stakeholders and optimising forest surveillance efforts across the biosecurity continuum using a risk-based approach.

Programs

State and regional weed and pest animal committees

The State Weed Committee is responsible for ensuring a coordinated and strategic approach to weed management in NSW and provides strategic planning advice to Regional Weed Committees to ensure consistent approaches across the State.

The State Pest Animal Committee was established in 2017. Its key responsibilities include overseeing a consistent approach to the formation and ongoing operation of Regional Pest Animal Committees and advising on regional and State pest animal policy and regulation.

The NSW Government established regional weed and pest animal committees in each Local Land Services area. These committees coordinate regional pest animal and weed management activities on both public and private land and have developed 11 Regional Strategic Weed Management Plans and Regional Strategic Pest Animal Management Plans. The plans identify actions that can help land managers to manage weeds and pest animals on their land under the NSW Biosecurity Act.

Management of invasive species by the National Parks and Wildlife Service

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) undertakes a range of pest animal and weed control programs to minimise impacts on biodiversity, protected areas, the community and neighbouring primary production. This involves managing already established as well as new and emerging invasive species.

Aerial shooting and aerial baiting program

The 2019–20 bushfires impacted 2.7 million hectares of NSW national parks. After fire, native animals are particularly vulnerable to predation by foxes and feral cats as there is less cover for them, which makes it easier for cats and foxes to hunt. Feral herbivores also compete with native animals for food and inhibit the regeneration of vegetation after fire.

Scientists have identified feral animal control as one of the highest priorities for protecting our wildlife and promoting recovery after the bushfires.

NPWS is implementing the largest aerial shooting and aerial baiting program ever delivered on the park estate, targeting in particular foxes, goats, pigs and deer. This includes working closely with neighbours and other agencies such as Local Land Services (LLS) to implement cross-tenure feral animal and weed control.

The level of aerial shooting across NSW parks in the 12 months to 30 June 2021 represents a tripling of effort compared to the annual average level of effort across the decade from 2010 to 2020. The post-fire aerial baiting program in the 12 months to 30 June 2021 represents a five-fold increase in effort compared to the annual average level of effort across the period 2015 to 2020. When mustering and other forms of feral animal control (such as ground shooting, trapping and mustering) are included, NPWS has removed more than 55,102 feral animals across the national park estate since 1 January 2020.

Feral predator-free areas

NPWS management of invasive species is a key component of the NSW Government program to establish a network of feral predator-free areas on national parks. The initiative will help turn back the tide of extinctions through the establishment of large feral animal-free areas which enable the return of locally extinct mammals and increase the population of extant threatened species at risk from predation.

As part of this program, fenced areas have been established at Sturt National Park, Mallee Cliffs National Park and the Pilliga State Conservation Area. As of December 2021, feral-free fences are protecting just under 20,000 ha of land. On 18 December 2020, the NSW Government announced the establishment of four new feral predator-free areas.

The extended project proposes one of the most significant threatened fauna restoration projects in NSW history, enabling the reintroduction of 28 locally extinct species (23 of them threatened) and delivering a measurable conservation benefit for at least another 30 threatened species which, in turn, will help restore essential ecosystem function and processes (see Protected Areas and Conservation topic).

Feral cat management

NPWS undertakes targeted shooting and trapping of feral cats in priority areas to protect critical populations of threatened species, as well as incidental shooting during other management programs.

Through the Environmental Trust, the NSW Government has invested an additional $14.6 million, over five years, in a feral cat research project with the University of New England, in partnership with NPWS and the Department of Primary Industries. The project is designed to develop and demonstrate new approaches to feral cat management and will include trials of baiting. The total investment in this project over five years will be over $30 million. This is the largest ever investment by the NSW Government in feral cat research and control.

Feral deer management

In July 2019, NPWS commenced a $16.9 million cross-tenure project to develop new cost-effective, humane and coordinated feral deer control techniques. This includes $9.2 million of funding from the Environmental Trust.

The eight-year project is taking place in southern Kosciuszko National Park and adjacent private farming lands. The project is being delivered in collaboration with private landholders, Local Land Services and the tertiary education sector, and is relevant to locations across NSW and Australia.

The project has nearly completed its first phase, focused on collecting baseline data, establishing robust monitoring infrastructure, and building effective stakeholder relationships. This includes installing camera arrays to track deer movement, establishment of vegetation monitoring sites, and using thermal imagery to establish existing deer population data.

Lord Howe Island rodent eradication program

In 2019, a rodent eradication program, funded largely by the NSW Environmental Trust and Commonwealth Government, was delivered to remove all introduced house mice and black rats was undertaken to protect Lord Howe Island’s World Heritage and biodiversity values. Between October 2019 and April 2021, there were no confirmed live rodent sightings or activity. In this time, Lord Howe Island has seen remarkable ecological benefits, particularly to its woodhen, seabird, threatened plants and invertebrate populations.

A plan to address ongoing biosecurity risks is being executed. In April 2021, rodent activity was again detected, and a comprehensive response initiated. As of September 2021, 96 rats have been destroyed. A scientific assessment has commenced to determine if detected rodents are new arrivals or survivors of the original eradication. This will inform future biosecurity measures to protect this critical World Heritage habitat.

Saving our Species

Biosecurity control measures provide a general level of protection for species and ecosystems. More specific priorities for ensuring threatened species are secured in the wild are set in Saving our Species. Many of the actions to recover terrestrial threatened species under the program focus on controlling pest animals and weeds, which affect over 70% of listed threatened species, populations and ecological communities.

For more information on threatened species protection and Saving Our Species, see the topic.

Containment lines

The best method to effectively manage new and emerging invasive species is to first eradicate them or to at least contain them before they spread enough to cause significant environmental harm. Where eradication is not feasible, establishing strategic containment lines can be an effective method of control. Containment lines are mapped lines, often delineated along a natural feature, such as a river or along local government or other management boundaries.

A containment line is placed around the core distribution of the weed or pest. Any population outside the containment line and any isolated populations well away from the core distribution area are then fragmented or depleted and can be eradicated. Control and impact reduction activities continue in the core infestation. A long-running example of the benefits of containment are the national bitou bush containment lines in northern and southern NSW. Bitou bush infestations are eradicated south and north of the containment lines near Jervis Bay and Byron Bay respectively, preventing spread into Queensland, Victoria and southern NSW. More information on bitou bush containment can be found in the Bitou bush management manual.

Cane Toad Biosecurity Zone

A Cane Toad Biosecurity Zone has been established south of the Clarence River and west of the Summerland Way with the aim of eradicating cane toads from this area.

Since December 2018, NPWS has partnered with Clarence Landcare Inc., Border Ranges-Richmond Valley Landcare, Clarence Valley Conservation in Action (CVCIA) and specialist ecologists to greatly increase control in the Biosecurity Zone. The western extent of the toad population has been delineated and a coordinated community engagement program launched.

Extensive new private lands have also come under control, considered essential as much of the project area consists of high-risk agricultural and rural-residential development. More than 80% of property owners now control toads in some areas adjacent to the containment line.

The project supports the highly successful CVCIA volunteers. Two new toad-busting groups have been formed to fill geographic gaps in control with citizens mobilised to monitor and control new incursions in townships. Aboriginal custodians have been engaged to undertake control.

In addition to coordinating control efforts and removing large numbers of cane toads from the landscape, Landcare partners have identified new incursions and investigated public reports lodged with the Department of Primary Industries. Community training and the NPWS Facebook page are used for public education to prevent misidentification and harm to native frogs.

Data continues to be added to the NPWS Pest and Weed Information System, but so far more than 226,000 cane toads have been killed over the past 2.5 years, including 83,000 in 2020–21. This does not include tadpoles and eggs, which were estimated to total 466,501 in 2019–20 alone.

National Carp Control Plan

The National Carp Control Plan (NCCP) includes all Australian jurisdictions working in partnership to identify safe, effective and integrated measures to control Australia’s carp populations.

Between 2016 and 2019, the NSW Government participated in developing the NCCP. The centrepiece of the strategy was multiple assessments of the safety and efficacy of a species-specific viral biological control agent for carp, dubbed ‘Cyprinid herpesvirus-3’. Development of the plan incorporated the results of 18 research projects, numerous planning investigations and feasibility studies, commissioned as part of the NCCP.

A draft plan was submitted to the Commonwealth in January 2020. Upon completion of some supplementary research, the final plan will be considered by all Australian governments and then released publicly. NSW continues to work with the Commonwealth to progress registration of the virus as a biological control agent and prepare for its potential release (if agreed). Further public consultation, legislative approvals and detailed implementation planning will be needed before this can occur.

Future opportunities

Between 2008 and 2017, the NSW Government spent $107 million on significant biosecurity plant and animal disease and pest incident responses in NSW.

Future opportunities include:

- continual improvements to surveillance and biosecurity measures to help prevent new and potentially invasive species from threatening natural ecosystems and the productivity of farming systems

- development of biological control solutions and other new techniques, such as advance remote detection tools, which will help provide opportunities to effectively and affordably manage widespread invasive species

- better understanding of pathogens that threaten native plants and animals, which continue to emerge as an increasing threat to natural systems and are likely to present challenges for effective management and control.

References

Fleming PJS, Ballard G & Tarrant M 2014, Aerial Baiting for Wild Dogs, project ON-00047 (ex AWI WP477), final report to Australian Wool Innovation Ltd, Sydney