Summary

The public reserve system covers about 7.59 million hectares or 9.5% of land in NSW. Conservation on private land is also important in protecting the natural environment in NSW.

Since 2015, the area of land in national parks and nature reserves has increased by 31,900 hectares. The representativeness and comprehensiveness of protected areas in NSW is improving with significant additions to underrepresented areas, but some bioregions and vegetation classes are still underrepresented, particularly in the central and western regions.

Conservation on Crown and private land supplements the protected area network and provides vegetation corridors linking larger public reserves. Some natural ecosystems protected on these lands are underrepresented or not present in public reserves. The Biodiversity Conservation Trust promotes conservation on private land, encouraging landholders to voluntarily enter into one of three types of private land conservation agreements for environment management and protection to conserve biodiversity.

There has been little change to the management or extent of marine protected areas over the past three years, but the NSW Government is exploring options to enhance marine biodiversity protection in the Hawkesbury Shelf marine bioregion (between Wollongong and Sydney).

The number of parks on land jointly managed or owned by Aboriginal people has increased.

Related topics: Invasive species | Wetlands | Native fauna | Threatened species | Climate change

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Area of terrestrial reserve system |

|

Getting better | ✔✔✔ |

| Growth in off-reserve protection |

|

Getting better | ✔✔ |

| Protected areas jointly managed or owned by Aboriginal people |

|

Getting better | ✔✔✔ |

| Area of marine protection |

|

Stable | ✔✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are explained in How to use the report

Context

Protected areas of land and water in original or close-to-original natural condition are the cornerstone of nature conservation efforts in NSW.

The State's public land reserve system has a substantial network of protected areas such as national parks and flora reserves that:

- conserves representative areas of habitats and ecosystems, plant and animal species, and significant geological features and landforms

- protects areas of significant Aboriginal and European cultural heritage

- provides opportunities for recreation and education.

Crown reserves can supplement nearby protected areas and may include:

- Crown land reserved for purposes such as environment protection and soil conservation under the Crown Land Management Act 2016

- State parks reserved primarily for nature-based recreation and managed by various trusts under the Crown Land Management Act 2016

- natural areas administered by trusts under the Crown Land Management Act, and managed by local councils

- Local land services travelling stock routes

- former perpetual leases converted to freehold under the Crown Lands Act 1989 with covenants protecting existing environmental values.

Other important supplements to public reserves are privately-owned areas managed for conservation under legal agreements with landowners and landholders.

The State's marine-protected areas provide a large network of marine parks and aquatic reserves. One objective of marine parks and aquatic reserves is to conserve biodiversity and maintain the ecosystems of bioregions in NSW waters. Other objectives are to:

- enable resources to be used in an ecologically sustainable manner

- enable the park or reserve to be used for scientific research and education

- provide opportunities for public appreciation and enjoyment

- support Aboriginal cultural uses.

Aboriginal people's relationship with Country

The NSW Government and the NSW Constitution acknowledge that Aboriginal people are the original custodians of the lands and waters, and have a spiritual, social, cultural and economic relationship with their traditional lands and waters.

The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) commits to involving Aboriginal communities in the management of all national parks and reserves. This is consistent with the OEH principles document Aboriginal People, the Environment and Conservation, and the staff of National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) Statement of reconciliation.

Through joint management agreements, OEH and Aboriginal people share responsibility for managing national parks and reserves. OEH has 31 joint management agreements with Aboriginal traditional owners, covering approximately 2.1 million hectares. Negotiations for two more agreements will be finalised in 2018 and negotiations for a further nine agreements are planned.

OEH also has an annual funding program for Aboriginal Park Partnership Projects for all parks and reserves across the State. Partnerships between Aboriginal people and NPWS recognise that:

- all parks and reserves are part of Aboriginal peoples’ Country and are places where Aboriginal people can care for and access their Country and its resources. NPWS parks and reserves play an important role in maintaining Aboriginal culture and connection to Country

- Aboriginal communities obtain cultural, social and economic benefits through being involved in park management

- OEH, in partnership with the Aboriginal community, can protect and interpret cultural heritage and apply Aboriginal knowledge to land management and the conservation of cultural and natural values

- visitors to parks gain a greater understanding of Aboriginal cultural values and an enriched experience through interaction with Aboriginal people.

The Forestry Corporation of NSW works with Aboriginal communities in some State forests to conserve the qualities and attributes of places that have spiritual, historic, scientific or social value.

Object 1.3(e) of the Crown Land Management Act 2016 facilitates the use of Crown land by the Aboriginal people of NSW and, where appropriate, to enable the co-management of dedicated or reserved Crown land.

The Marine Estate Management Authority has worked closely with Aboriginal communities over the past three years. This has been to identify threats to Aboriginal culture and heritage in coastal and marine environments and to develop actions to address these threats, for inclusion in a Marine Estate Management Strategy. Employment and improved involvement in the management of Sea Country are key outcomes.

Status and Trends

Land-based formal reserves

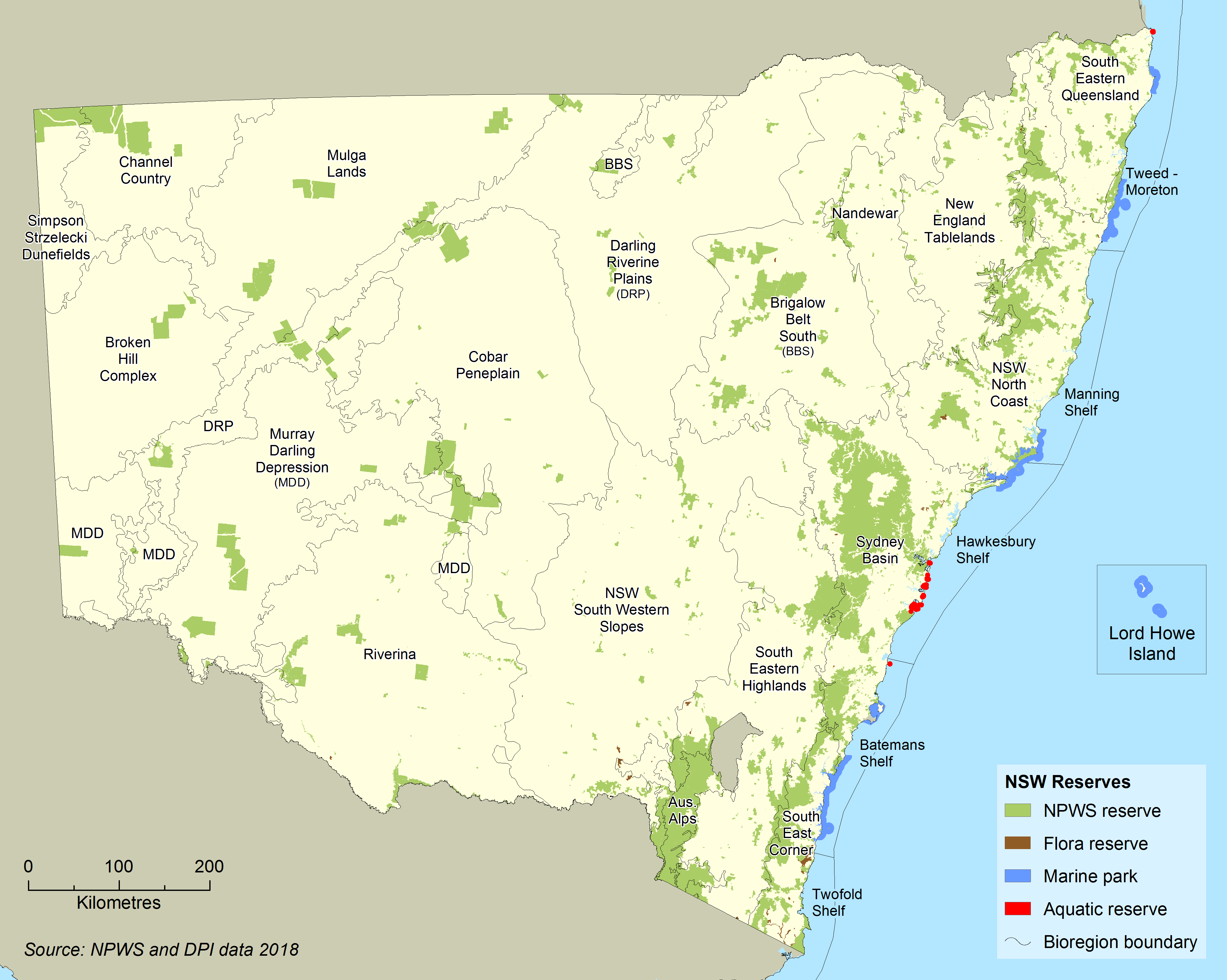

Protected areas that meet formal reserve standards under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Protected Areas Categories System are depicted in Map 14.1.

At 1 January 2018, formal reserves comprised at least 9.5% of NSW, and included:

- public reserves protected under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act), comprising 872 reserves totalling 7,142,675 hectares or approximately 9% of the State

- land reserved for conservation as flora reserves under the Forestry Act 2012

- land reserved for environment and heritage protection as formal Crown reserves such as Barigan Heritage Lands Reserve east of Mudgee (25,774 hectares) but not shown in Map 14.1.

Reserves established under the NPW Act include national parks, nature reserves, state conservation areas, karst conservation reserves, historic sites and Aboriginal areas. State conservation areas, for example, allow resource exploration and mining as well as protecting natural and cultural values.

Other types of land protected for nature conservation are considered later in this section.

Map 14.1: NPWS reserves, flora reserves, marine parks and aquatic reserves

Additions to land-based national parks and reserves since 2015

Since the 2015 State of the Environment report (EPA 2015), there were 58 additions to NPWS parks and reserves, totalling 31,900 hectares. The largest areas of additions included:

- Kalyarr National Park (20,240 hectares added)

- Yathong Nature Reserve (4,151 hectares added)

- Culgoa National Park (2,286 hectares added)

- Captains Creek Nature Reserve (1,188 hectares added)

- Oxley Wild Rivers National Park (765 hectares added)

- Dananbilla Nature Reserve (541 hectares added).

Figures 14.1 and 14.2 show additions to national parks and reserves since 2009 by area and number of reserves.

There were fewer additions to the public reserve system from 2015–18 than from 2012–15, due to:

- ending of National Reserve System funding

- lack of available public land suitable for transfer

- a focus on higher value land for purchase in eastern NSW

- consolidation of reserve boundaries to improve management effectiveness and efficiencies

- an increasing focus on private land conservation to complement public reserves.

Figure 14.1: Yearly increase in area (hectares) of national parks and reserves in NSW since 2009

Figure 14.2: Yearly increase in number of national parks and reserves in NSW since 2009

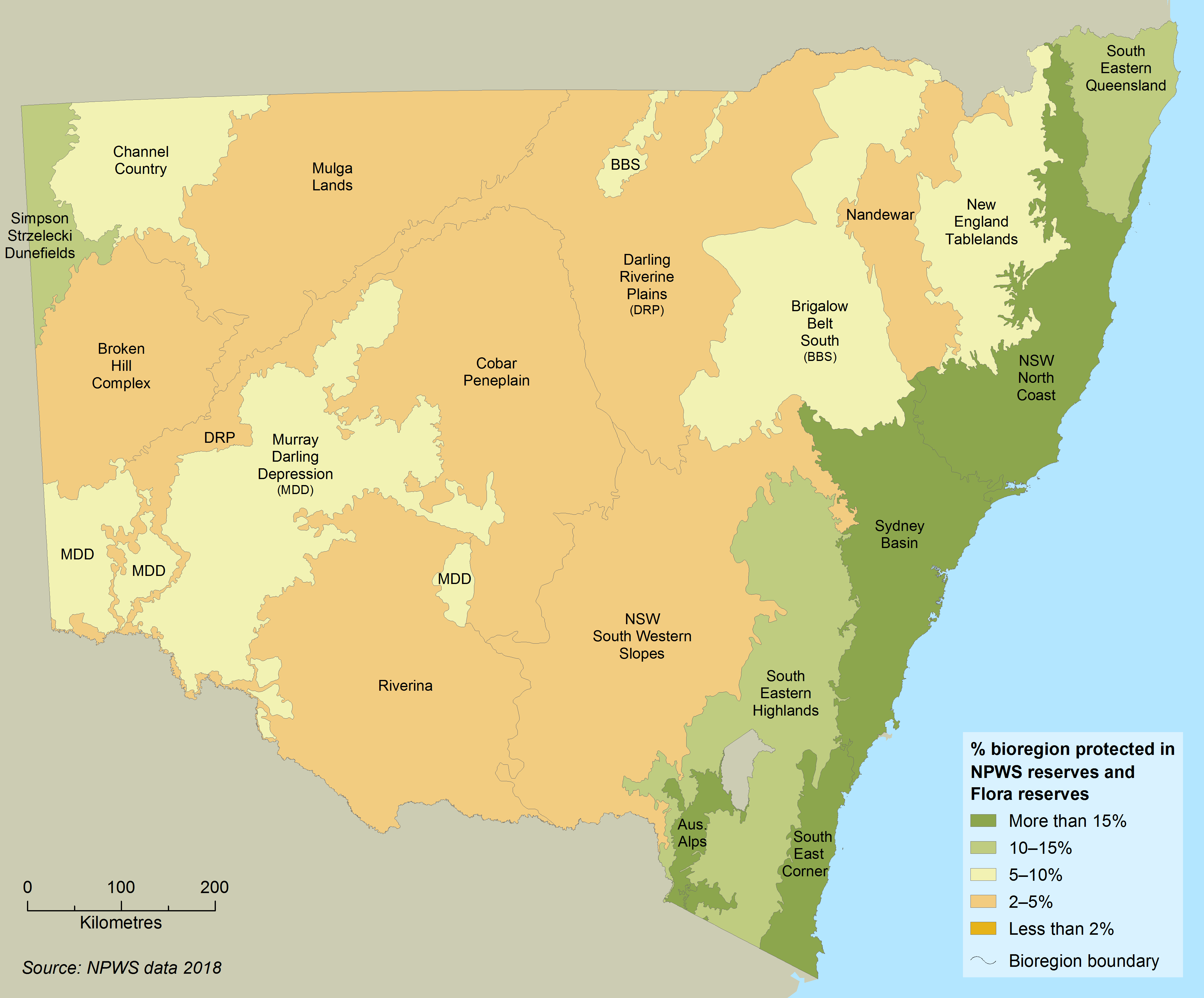

Representation of protected land in NSW bioregions

NSW national parks and reserves are selected according to the conservation principles of comprehensiveness, adequacy and representativeness (CAR):

- comprehensiveness refers to conserving samples of each ecosystem and bioregion, in protected areas

- adequacy refers to how much of each ecosystem should be protected to provide ecological viability and adequately conserve populations, species and communities

- representativeness means protecting the full range of biological variation in each ecosystem’s geographic range.

Bioregions are relatively large land areas characterised by natural features and environmental processes that influence the functions of entire ecosystems. Currently in NSW, the most comprehensively protected ecosystems are those on the steep ranges of eastern NSW, parts of the coast, and the Australian Alps. Poorly protected ecosystems include most ecosystems in far western NSW, the northern, central and southern highlands and on the western slopes; and those on the richer soils of the coastal lowlands.

Map 14.2 shows the proportion of land in public reserves in each of the 18 bioregions of NSW. The bioregions of eastern NSW are generally well‑represented compared with bioregions in the centre and far west of the State which are mostly underrepresented.

- Of the 18 bioregions, four still have fewer than 50% of their ecosystems included in public reserves.

- Thirty of the 131 subregions in NSW still have under half their ecosystems protected in reserves.

- Many poorly represented bioregions, particularly in central NSW, incorporate large areas of highly fragmented vegetation. With extensive areas used for other land uses, there are limited opportunities to add viable lands to reserves.

Private land conservation can help protect additional ecosystems in conservation priority investment areas.

Map 14.2: Bioregional reservation in NSW

Notes:

The NSW Government’s Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy is guiding investment in private land conservation to improve outcomes for underrepresented bioregions.

Private land conservation in NSW

With less than 10% of NSW conserved in national parks and reserves and more than 70% of the State under private ownership or Crown lease, private land conservation plays a vital role in conserving additional biodiversity in NSW. Around 3.9% of NSW has some form of private land conservation management in place (see Table 14.1).

Table 14.1: Private land conservation in NSW

| Conservation mechanisms | Number | Area protected (hectares) |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation agreements | 467 | 156,720 |

| Wildlife refuges | 687 | 1,889,135 |

| Nature Conservation Trust agreements | 131 | 56,439 |

| Incentive property vegetation plans | 2045 | 1,003,867 |

| Registered property agreements | 317 | 50,635 |

| BioBanking agreements | 92 | 10,802 |

| Land for Wildlife (Community Environment Network) | 1125 | 87,242 |

| Indigenous Protected Areas | 10 | 16,000 |

| Total | 3,128,195 |

In addition to areas shown in Table 14.1 are covenants on converted perpetual leases that protect environmental values. There are approximately 3,500 covenants, comprising an area of approximately one million hectares.

Conservation principles on other public land

Forests NSW conservation zones

The Forestry Corporation uses a zoning system in State forests that identifies areas set aside for conservation.

Through this zoning system about 40,000 hectares of State forest are formally protected as flora reserve, 486,000 hectares of State forest (22%) excluded from harvesting for conservation reasons, and a further 544,964 hectares excluded from harvesting for silvicultural reasons. These areas, 47% of the total area of State forests, make a significant contribution to protected areas in NSW.

Travelling stock routes

Travelling stock routes (TSRs) are authorised thoroughfares on Crown land for moving stock from one location to another. On a TSR, grass verges are wider and property fences are set back further from the road than usual, providing feeding stops for travelling stock.

TSRs are often found in environments that are poorly represented in public reserves. Although narrow and modified, TSRs tend to be well vegetated and in better condition than the surrounding land. The conservation values of approximately 700,000 hectares of TSRs in eastern and central NSW are still to be comprehensively assessed. The generally much wider TSRs of western NSW are largely situated on lands under secure Western lands lease tenure.

Table 14.2: Travelling stock routes in NSW

| Region | Area in hectares of travelling stock route | Bioregion (hectares) | % of bioregion in a travelling stock route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Alps | 272.7 | 464,297.5 | 0.06% |

| Brigalow Belt South | 83,767.9 | 5,624,738.4 | 1.49% |

| Broken Hill Complex | 151,042.7 | 3,763,317.7 | 4.01% |

| Channel Country | 117,549.4 | 2,340,662.2 | 5.02% |

| Cobar Peneplain | 230,967.3 | 7,377,221.2 | 3.13% |

| Darling Riverine Plains | 474,827.7 | 9,419,258.4 | 5.04% |

| Mulga Lands | 242,205.2 | 6,591,283.3 | 3.67% |

| Murray Darling Depression | 319,509.0 | 7,935,880.5 | 4.03% |

| Nandewar | 24,630.6 | 2,074,881.9 | 1.19% |

| New England Tableland | 29,063.2 | 2,860,297.9 | 1.02% |

| NSW North Coast | 9,271.1 | 3,962,537.5 | 0.23% |

| NSW South Western Slopes | 52,696.5 | 8,103,373.4 | 0.65% |

| Riverina | 222,040.5 | 7,022,691.5 | 3.16% |

| Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields | 14,709.7 | 1,095,796.6 | 1.34% |

| South East Corner | 821.3 | 1,153,600.6 | 0.07% |

| South Eastern Highlands | 7,274.5 | 4,989,020.1 | 0.15% |

| South Eastern Queensland (NSW area) | 4,959.6 | 1,647,040.8 | 0.30% |

| Sydney Basin | 2,230.5 | 3,573,565.9 | 0.06% |

| Total, and average percent | 1,987,839.3 | 79,999,465.4 | 2.48% |

Marine protected areas

The Marine Estate Management Act 2014, which commenced on 19 December 2014, provides for the declaration and management of marine parks and aquatic reserves, which are managed by the Department of Primary Industries. Management rules are contained in the Marine Estate Management (Management Rules) Regulation 1999.

The aquatic reserve notification gazetted in 2015 under the Marine Estate Management Act 2014 sets out the activities prohibited in each aquatic reserve.

Extent and types of marine protected areas

Current NSW marine protected areas (Map 14.3) include:

- Six multiple-use marine parks, which cover around 34% (approximately 345,000 hectares) of NSW waters.

- 12 aquatic reserves, which cover around 2,000 hectares of NSW waters.

- National park and nature reserve areas occurring below the astronomical high tide level, which include around 20,000 hectares of estuarine and oceanic habitats.

- The northern and southern regions of NSW, which are well represented by marine parks.

- The central region, which incorporates the Hawkesbury Shelf marine bioregion. The region does not contain a marine park at present but does contain all but one of the 12 aquatic reserves.

- The Twofold Shelf bioregion which only extends into the far south of NSW, being mostly situated in eastern Victoria. There are no marine parks or aquatic reserves on this small section of the NSW coast.

Marine parks in NSW are managed according to zones consistent with the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) categories for protected area management. There are four types of marine zones:

- ‘sanctuary’ (IUCN II) – the highest level of protection for biodiversity and natural and cultural features

- ‘habitat protection’ (IUCN IV) - protects physical and biological habitats by reducing high impact activities

- ‘general use’ (IUCN VI) - provides for a wide range of environmentally sustainable activities

- ‘special purpose’ (IUCN VI) – special management arrangements including protection of Aboriginal and other cultural features, or for marine facilities, or for specific park management.

The total area of sanctuary (or no-take) zones is around 65,630 hectares. In June 2018, this area decreased slightly as a result of the NSW Government's decision to rezone 10 sites from 'sanctuary zone' to 'habitat protection zone' to make shore-based recreational line fishing lawful. Overall this decision resulted in a 0.05% reduction in sanctuary zone area, from 6.49 to 6.44% of the NSW marine estate.

Map 14.3: Marine parks and aquatic reserves along the NSW coast

Pressures

Threats to national parks and reserves

Weeds

Weeds are a significant problem, endangering threatened species, threatened ecological communities and Aboriginal sites including rock engravings and grinding grooves. It is important to deal with new and emerging weeds before they start threatening native plants and animals and Aboriginal cultural sites. See ‘Responses’ for information about actions being taken.

The most pervasive widespread weeds in reserves are:

- bitou bush

- lantana

- African olive

- scotch broom

- introduced perennial grasses such as serrated tussock

- exotic vines such as madeira vine.

These weeds are listed as key threatening processes under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

Pest animals

Introduced pest animals including foxes, wild dogs, rabbits, deer and feral cats, goats, and pigs are widespread across all of NSW, including in national parks and reserves. Pest animals threaten native flora and fauna, including threatened species, through competition, predation and habitat degradation. As they are present on public and private land, the NSW Government, local councils, and private landowners and landholders must work together to manage them effectively. See ‘Responses’ for information about actions being taken.

Horses, wild deer and cane toads present localised issues in some reserves. For example, some alpine ecosystems of the Snowy Mountains are under significant and increasing pressure from wild horse populations. Hard-hoofed animals cause significant ground and stream bank disturbance, damaging vegetation and threatened species habitat.

Fire

Inappropriate fire regimes may threaten biodiversity in reserves, though planning and hazard reduction burns reduce the severity of impacts and protect life and property.

- In 2016–17, there were 296 fires in national parks, affecting an area of 41,290 hectares. NPWS and Forestry Corporation firefighters also assisted with 97 fires outside parks.

- In 2017–18 (as at 30 May) there had been 482 fires in national parks, affecting an area of 121,530 hectares. NPWS firefighters also assisted with 107 fires outside parks.

- Forestry Corporation reported that the forest estate was broadly protected from fire during 2016–17. Like NPWS, it deployed crews to assist on significant fires on private property and other land as part of NSW’s coordinated firefighting effort.

During the last 10 years, a third of fires in reserves were caused by lightning strike, which burnt 59% of the total area affected by fire. Arson or other suspicious causes accounted for 29% of the fires, or 9% of the area burnt.

Habitat and species isolation

Habitat and species isolation can occur when there are limited vegetation corridors or natural areas between reserves and other key habitats. This can impede movement of animals across landscapes and reduce breeding and genetic variation. Land use changes such as land being developed for housing or agriculture, or land clearing next to reserve boundaries can make it difficult to maintain habitat connectivity.

Illegal activities

The most widely reported illegal activities in NSW national parks are:

- waste dumping

- unregistered off-track trail bike riding

- vandalism

- hunting.

These activities have a negative effect on visitors' enjoyment and safety. They also affect biodiversity, particularly threatened animals, plants and endangered ecological communities; and cultural heritage sites.

Other activities that threaten reserves include timber getting, antisocial behaviour, arson, collecting plants or other materials and stock encroachments from neighbouring properties.

Climate change

Predicted climate change impacts include:

- loss of plant and animal communities and species with a restricted range or diminished capacity to adapt to changes in climate

- increased number and severity of bushfires

- increased impacts on coastal reserves from storms and sea level rise

- increased weed invasion

Some of the natural systems affected or likely to be affected include:

- threatened seabird habitats

- freshwater lagoons

- saltmarsh areas

- sub-alpine habitats

- sand dunes

- rainforests.

Threats to these areas can result in decreased species distribution and abundance.

Threats to marine protected areas

In 2017 the NSW Marine Estate Management Authority completed a statewide threat and risk assessment to the environmental assets of the marine estate, as well as to the social, cultural and economic benefits derived from the marine estate. Lord Howe Island Marine Park was excluded from this assessment.

The top five priority threats identified were:

- urban stormwater discharge

- estuary entrance modifications (affecting water flows)

- runoff from agricultural activities

- clearing riparian and adjacent habitat, including draining wetlands

- climate change.

Community opinion

Surveys of the community conducted as part of the NSW Marine Estate Management Authority’s threat and risk assessment identified that the community cares about the health of the State’s estuaries and marine waters; and that clean water, healthy habitats and abundant and diverse marine biodiversity underpins the NSW community's social and cultural wellbeing (Sweeney Research, 2014). Priority threats were considered to be:

- littering and marine debris

- oil and chemical spills

- water pollution from sediment or runoff.

Overcrowding, conflicting use and lack of public access were also recognised as potential social threats.

Perceived threats to economic viability were identified as water pollution, loss of natural areas and increasing costs of accessing the marine environment. The diversity and abundance of marine life and the natural beauty of the marine environment were seen as being key economic values for nature-based and regional tourism.

Threats to conservation on private land

The pressures that affect protected areas on private land are similar to those affecting public reserves. These include weeds and pest animals, fire, habitat isolation, illegal activities including clearing of native vegetation, the impacts of stock encroachment and neighbouring land uses.

Land managers may need to address potential threats from other land uses such as agriculture when they are not compatible with conservation values. Unpredictable events, such as bushfires or sustained drought, may exacerbate these threats.

Responses

Legislation and policy

Review of land-based conservation legislation

In 2014, the NSW Minister for the Environment established an independent panel to review the Native Vegetation Act 2003, the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, the Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001 and parts of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. The aims of the review were to recommend legislation that was simpler, more streamlined and effective. The panel provided 43 recommendations in its report (Byron et al. 2014) including some concerning private land conservation.

The NSW Government accepted all the recommendations, and in 2016 rolled out a program of reforms, including the legislative changes outlined in Table 14.3.

Table 14.3: Recent reforms to conservation legislation

| Legislation | Change | What’s in place now? |

|---|---|---|

| Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 | Repealed | Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 |

| Native Vegetation Act 2003 | Repealed | Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 |

| Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001 | Repealed | Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 Biodiversity Conservation Trust established |

| National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 | Animal and plant provisions repealed | Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 |

| Local Land Services Act 2013 Local Land Services Regulation 2014 | Amended | Local Land Services Act 2013 Local Land Services Regulation 2014 |

| New | State Environmental Planning Policy (Vegetation in Non-Rural Areas) 2017 |

The Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the Local Land Services Act 2013 are the main Acts governing land management and biodiversity conservation and commenced on 25 August 2017. Applicants for managing native vegetation under Division 6 of the Local Land Services Act 2013 have a requirement under the Land Management (Native Vegetation) Code 2018 to manage land in perpetuity for conservation.

The Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy 2018 guides investment in private land conservation.

Other key components are identified below:

Biodiversity Offsets Scheme

The Biodiversity Offsets Scheme replaces a previously fragmented approach to biodiversity conservation and development and updates it with a single framework that captures all types of developments that are likely to have a significant impact on biodiversity. It applies to local developments, major projects, the clearing of native vegetation where State Environmental Planning Policy (Vegetation in Non-Rural Areas) 2017 applies and clearing on rural land that requires Native Vegetation Panel approval. Public authorities can also opt in to use the scheme.

Under the scheme, applicants must avoid impacts on biodiversity if possible, then minimise impacts that cannot be avoided. Impacts that cannot be avoided or minimised may be offset by buying biodiversity offset credits or transferring this obligation to the Biodiversity Conservation Trust by paying into the Biodiversity Conservation Fund. Proponents may also be able to use other agreed conservation measures, such as funding biodiversity conservation actions or mine site rehabilitation (for major mining projects only).

The Biodiversity Offsets Scheme also introduces a new pathway of strategic biodiversity certification to encourage upfront consideration of biodiversity conservation in significant regional development and planning processes. It is intended to address the cumulative impacts of development and deliver more certainty about the development potential and conservation outcomes for an area.

Policy tools, such as Biodiversity Offset Scheme, can be effective mechanisms for balancing the competing demands of conservation and development. Strong public policy, scientific monitoring, and conservation efforts on private land to improve connectivity and protection, are important to bolster the success of biodiversity offset schemes and biodiversity outcomes. See also Hanford et. al. (2017), Maron et. al (2015) and Byron et. al (2014).

Developers may meet their offset obligations by dedicating land for reservation under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974.

Biodiversity Assessment Method

For all developments entering the biodiversity offsets scheme, specially accredited assessors must apply the Biodiversity Assessment Method to measure:

- the impacts on biodiversity from all developments

- the biodiversity gained at an offset site.

This scientifically-based method helps developers and landholders to identify and measure the potential impacts of their activities on the natural environment, and take appropriate steps to avoid, minimise or offset those impacts.

Private land conservation and the Biodiversity Conservation Trust

Under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, private landowners can voluntarily enter into one of three types of private land conservation agreements:

- Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements are for landholders wishing to generate and sell biodiversity credits under the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme. They protect biodiversity on the land in perpetuity.

- Conservation Agreements conserve and manage biodiversity on an area of land and may be in perpetuity or for a stated timeframe.

- Wildlife Refuge Agreements are for landholders who wish to protect the biodiversity on their property but do not wish to enter into a permanent agreement.

These agreements are administered by the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust (BCT). The purpose of this statutory body is to protect and enhance biodiversity by:

- encouraging landholders to enter into cooperative arrangements for natural environment management and protection to conserve biodiversity on their land

- seeking strategic biodiversity offsets to compensate for the loss of biodiversity due to development and other activities

- providing mechanisms for biodiversity conservation

- promoting public knowledge, appreciation and understanding of biodiversity and its conservation.

In the first five years of the Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy’s operation, the NSW Government has invested $240 million in encouraging biodiversity conservation on private land and allocated $70 million thereafter, depending on performance reviews.

Reforms to Aboriginal cultural heritage

The NSW Government has proposed a new system for managing and conserving Aboriginal cultural heritage in NSW, supported by a legal framework.

In February 2018, the NSW Government released the draft Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Bill 2018 for public consultation. A series of public information sessions and workshops were held from September 2017 to April 2018. The feedback received is being considered in finalising the draft bill.

Programs

Plans of management for national parks and reserves

Plans of management are legal documents that guide how a park or reserve will be sustainably managed. As at 1 January 2018, 387 plans of management had been adopted, covering 591 parks and reserves. More than 6 million hectares are now covered by plans, representing around 85% of protected areas. Parks without a plan generally have a statement of management intent.

A statement of management intent is an interim document outlining the management priorities for a park based on its key values and major threats to these values. They also reference existing strategies that may already be in place for that park, for example, a fire management strategy.

NSW Koala Strategy

On 6 May 2018, the NSW Government released the NSW Koala Strategy, committing $44.7 million to securing the future of koalas in the wild. This was in response to the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer’s 2016 independent review into the decline of koala populations in key areas of NSW.

The NSW Koala Strategy:

- will support a range of conservation actions over three years

- conserves over 24,000 hectares of land with prime koala habitat as koala parks and reserves to ensure the habitat is conserved, key habitat corridors are linked and safe homes are provided for koalas being returned to the wild

- sets a foundation for the government’s longer-term vision to stabilise and increase koala populations across NSW.

The NSW Koala Strategy is proposed to deliver:

- $20 million from the NSW Environmental Trust to purchase and permanently conserve land in national parks and reserves that contain priority koala habitat

- $3 million to build a new koala hospital at Port Stephens

- $3.3 million to fix priority road-kill hotspots across NSW

- $4.5 million to improve the care of sick or injured koalas

- $6.9 million to improve our knowledge of koalas, starting with the development of a statewide koala habitat information database

- $5 million to deliver local actions to protect koala populations, including through the Saving our Species program

- $2 million to research impacts of natural hazards and weather on koalas.

For more information on actions to protect threatened species, see the Threatened Species topic.

Reintroduction of locally extinct mammals

Since 2015, the NSW Government has been working with the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) to reintroduce locally extinct mammal species into selected public reserves. See the Threatened Species topic for more information.

Managing threats to national parks and reserves

Weed and pest management

The NSW Government works across agencies to manage weeds and pest animals.

The NPWS has developed 14 Regional Pest Management Strategies to prioritise pest and weed management across reserves. These strategies will be reviewed in early 2019 when the NPWS will revise critical priorities for addressing new and emerging pests, economic impacts, health and disease impacts, and threatened species.

Overall priorities for pest and weed management to protect threatened species are identified in the Saving our Species program (SOS). For more information on SOS, see the Threatened Species topic.

In response to statewide reviews of weed and pest animal management conducted by the Natural Resources Commission, the NSW Government has established a State Weed Committee and a State Pest Animal Committee, as well as 11 Regional Weed Committees and 11 Pest Animal Committees facilitated by local land services. The regional committees have developed weed and pest animal management plans, which identify opportunities for working collaboratively with public and private landholders to control pests and weeds.

An important weed management program in NSW is eradicating mouse-ear hawkweed and orange hawkweed from Kosciuszko National Park. These weeds could devastate most of south-eastern Australia, causing major environmental degradation and costs to agriculture. The NSW Government, in partnership with local land services, local councils and other stakeholders, is on track to eradicate these two weeds from NSW.

The NSW Government works closely with stakeholders including local land services and private land managers to tackle wild dog problems across the State under a national wild dog action plan.

The Crown Lands division of NSW Department of Industry manages threats through a pest and weed control program.

Fire management

Over the last five years, NPWS has prevented around 90% of fires that started in parks from spreading beyond park boundaries.

In 2017–18 (as at 30 June 2018), NPWS conducted hazard reduction burns on 95,830 hectares of land. This represents 71% of the NPWS annual target of 135,000 hectares, which is calculated on a rolling five-year average.

Hazard reduction burning strongly depends on weather conditions so there are limited opportunities. Since the start of the Enhanced Bushfire Management Program in 2011, NPWS has undertaken 80% of total hazard reduction burning in NSW, despite managing only 9% of the State’s land area.

The Forestry Corporation is a major firefighting authority in NSW and manages fire in more than 2.2 million hectares of native and planted forest. Hazard reduction burning reduces forest fuels that increase the potential intensity of a bushfire. During the fire season, the Forestry Corporation staffs a network of fire towers across the State to detect fires early and respond rapidly to them, giving crews more chance of managing fires while they are still relatively small.

The Crown Lands division manages threats to values in reserves through its bushfire risk mitigation program.

Climate change

The NSW Government conducts research to better understand the impacts of projected climate changes on sensitive ecosystems. Private land conservation is playing an increasingly important role in promoting ecologically sustainable development and building resilience to climate change. The 2018 Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy - the NSW Government strategy to guide investment in private land conservation - seeks to optimise biodiversity outcomes, improve landscape connectivity and build resilience to climate change.

See also the Climate Change topic in the present State of the Environment Report with specific reference to the Climate Change Policy Framework.

Managing threats to marine parks and aquatic reserves

The Marine Estate Management Strategy establishes the framework for managing threats to the entire NSW marine estate (including marine parks and aquatic reserves) through to 2028. Initiatives in the strategy detail management objectives, threats, stressors, management actions and resulting benefits. Announced in 2018, the Strategy will focus on the most urgent threats including actions to improve water quality, reduce litter, and deliver healthy habitats.

Funding of $45.7 million over two years has been allocated to achieve this and will also contribute to planning for climate change, protecting Aboriginal cultural heritage, reducing impacts on threatened and protected species, enhancing social, cultural and economic benefits and ensuring good governance. Initiatives will also ensure sustainable fishing and aquaculture, and safe and sustainable boating. The Strategy integrates with other coastal and marine reforms in NSW to achieve a more coordinated approach to management of the marine estate by all levels of government.

The Marine Estate Management Act 2014 requires the development of a statutory management plan for each marine park in NSW. Statutory management plans are being developed and will replace the current zoning and operational plans in place in each of NSW’s six marine parks. The plans will respond to localised threats and will document management objectives and actions, including zoning, compliance, education and communications. The new management planning process will first be piloted in Batemans Marine Park before being rolled out to the remaining marine parks.

Hawkesbury Shelf marine bioregion assessment

In 2018, the NSW Government commenced public consultation on a potential new marine park in the Newcastle, Sydney and Wollongong regions.

The proposal includes 25 distinct sites from Newcastle to Wollongong, or approximately 6.6% of the Hawkesbury Shelf Bioregion, to be protected in either sanctuary, conservation or special purpose zones. The aim is to reduce local or site-based threats while conserving marine biodiversity and allowing for a range of community benefits and uses. Community consultation on the proposal concluded on 27 September 2018 and the NSW Government is currently considering submissions to inform a final response.

Controlling threats to conservation on private land

The NSW Government helps private landholders to manage their land for long-term conservation and sustainable production by:

- providing information and incentive programs

- facilitating State or Federal tax concessions

- developing a support package through the Biodiversity Conservation Trust for landholders who enter into private land conservation agreements.

Future opportunities

Integrated approach to conservation

The NSW Government is taking an holistic approach to conserving biodiversity in national parks and on private land.

The public land acquisition program builds on the existing network of public land over large areas to help sustain resilient and viable ecosystems.

In regions where remnant vegetation is scarce, private land conservation is critical to prevent further biodiversity loss and improve connectivity in the landscape.

Local land services facilitate access to grants and work with landholders to ensure sustainable environmental, social and economic outcomes.

The government’s approach is guided by the Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy and the NSW National Parks System Directions Statement.

Review of NSW National Parks System Directions Statement

Every year, the NPWS acquires land for national parks by purchasing private land, and through public land transfers, donations and bequests.

The NSW National Parks Establishment Plan (OEH 2008) explains how and why new parks will be established and outlines the government’s targets and conservation priorities for acquiring new land and enhancing the parks system.

A new Establishment Plan is being finalised following public exhibition, and will set out the objectives, challenges and opportunities for increasing the national parks system over the next five years.

References

References for Protected Areas and Conservation

Byron N, Craik W, Keniry J & Possingham H 2014, A review of land-based conservation legislation in NSW: Final Report, Independent Biodiversity Legislation Review Panel, Office of Environment & Heritage, Sydney

EPA 2015, New South Wales State of the Environment 2015, Environment Protection Authority, Sydney [www.epa.nsw.gov.au/about-us/publications-and-reports/state-of-the-environment/state-of-the-environment-2015]

Hanford JK, Crowther MS & Hochuli DF 2017, ‘Effectiveness of vegetation‐based biodiversity offset metrics as surrogates for ants’, Conservation Biology, 31, pp. 161–71 [doi: 10.1111/cobi.12794]

Maron M, Bull JW, Evans MC & Gordon A 2015, ‘Locking in loss: Baselines of decline in Australian biodiversity offset policies’, Biological Conservation, 192, pp. 504–12 [doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.05.017]

OEH 2008, The NSW National Parks Establishment Plan 2008, Office of Environment & Heritage [http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/parks-reserves-and-protected-areas/establishing-new-parks-and-protected-areas/review-our-strategy]

Sweeney Research 2014, Marine Estate Community Survey, Marine Estate Management Authority, NSW Government, State of New South Wales [https://www.marine.nsw.gov.au/key-initiatives/marine-estate-community-survey]