Summary

Groundwater is often forgotten as it remains out of sight for most of its existence. It seeps (recharges) into the bedrock and may only appear as baseflow, adding to a river’s flow, or emerging from a spring. Sometimes it may be tapped into by a bore or it might bubble up from a mound spring or at the coast through sands. Or it may sit just below the surface in shallow or perched permeable rock (aquifers).

Why groundwater is important

Groundwater can occur in dry landscapes across NSW and sometimes appears as a desert oasis and as the only source of water. Aboriginal people have always known about groundwater. It’s been part of their Dreaming, their stories, lore, dances and art for up to 65,000 years or since time immemorial (or Day One). The understanding Aboriginal people have of connected water through thousands of generations of observation is something to celebrate, especially knowing that deep groundwater, such as in the Great Artesian Basin, is very old or ancient water.

The cultural and spiritual connection Aboriginal people have with groundwater ranges from a source of water for survival or economic benefit, to dreaming stories where cultural heroes and creators exist, such as the Rainbow Serpent. With this strong Aboriginal connection, the SoE Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group has put forward that NSW water managers must protect groundwater quality and quantity from impactful drawdown, pollution from industry, mining and agriculture and over-extraction to ensure cultural values of groundwater are protected.

Overall average annual extraction from metered groundwater sources in NSW is being managed under the compliance rules in water sharing plans. Knowledge of NSW groundwater-dependent ecosystems has improved, but some uncertainty remains about their extent and condition.

In NSW there are water sharing plans that manage groundwater and surface water. There are 14 Regions identified by NSW, each with a number of surface water and groundwater plans. Aboriginal people currently have little say in groundwater management and even less ownership of groundwater resources. This is in spite of their long, deep connection with it.

Groundwater is an important source for communities’ water supply, especially during droughts. Throughout NSW, 180 towns and villages rely on groundwater as their main water source for farming, irrigation and domestic use.

Certain ecosystems (groundwater-dependent ecosystems) depend either partially or mostly on the availability of groundwater to function when surface water is scarce.

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term extraction limit: Entitlement |

|

Stable | ✔✔ |

| Aquifer integrity |

|

Stable | ✔ |

| Groundwater quality |

|

Stable | ✔ |

| Condition of groundwater-dependent ecosystems* |

|

Unknown | ✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are defined in .

*While the condition of some groundwater-dependent ecosystems is known at a local level, the information in this report takes a statewide perspective

Spotlight figure 19 shows that groundwater extraction levels can fluctuate dramatically due to factors such as local sustainability levels and climatic conditions such as drought.

Status and Trends

Groundwater extraction increased between 2017–18 and 2019–20, reflecting significant demand for groundwater during a period of severe drought.

Demand for groundwater increased significantly between 2017–18 and 2019–20 from roughly 11% of the state’s overall metered water use to 27%, mainly due to extended and severe drought.

Overall, the quality of known groundwater sources is moderate, while the aquifer integrity is stable.

Water sharing plans rely heavily on groundwater sources. These plans manage the average annual extraction limits from metered groundwater sources under their compliance rules. Extraction from some inland alluvial groundwater sources in the Murray–Darling Basin and one porous rock groundwater source can at times exceed local sustainability limits. However, the overall level of groundwater extracted from all metered groundwater sources in NSW is much lower than the cumulative sustainable extraction limits.

Spotlight figure 19: Annual levels of NSW groundwater extraction from all metered groundwater systems 2001–02 to 2019–20

Pressures

Factors affecting the quality and availability of groundwater include excessive demand and extraction, saline intrusion and chemical contamination.

Responses

The Water Management Act 2000 legislates that all groundwater sources must be managed sustainably. Under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997, contaminated groundwater must be reported to the Minister administering the Water Management Act.

Other responses include various policies and programs.

- The NSW State Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Policy contains guidelines to protect and manage groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

- The NSW Aquifer Interference Policy balances the water requirements of towns, farmers, industry and the environment.

- The Cap and Pipe the Bores Program provides financial incentives for landowners to offset the costs of replacing uncapped artesian bores and open drains with rehabilitated bores and efficient pipeline systems.

Eleven water resource plans for groundwater sources in the Murray–Darling Basin were developed in 2020 and submitted for Commonwealth accreditation. These set out arrangements to share water, rules to meet environmental and water quality objectives and potential and emerging risks to groundwater quality and availability.

Related topics: | |

Context

Where surface water is available, groundwater is often seen as a supplementary water resource, as it has higher access costs. More importantly, however, it is often used as a tool to mitigate against surface water availability risk. However, in areas beyond the close proximity of rivers, groundwater is often the primary water resource. Widely used in agriculture and industry, groundwater is also the primary water source for domestic supplies in many NSW regional communities.

Groundwater management is heavily dependent on data from monitoring bores and groundwater extraction data. Managing groundwater is complex because each source is unique in composition and size and many factors determine how they function. This means groundwater sources cannot all be managed the same way.

The many ecosystems that depend on groundwater to survive include:

- highly specialised and endemic subterranean systems

- surface water systems (wetlands, rivers and lakes) connected to groundwater

- some land-based ecosystems.

Significant changes to the amount or quality of available groundwater can degrade ecosystems and affect human uses of this water. Because the groundwater often does not outcrop and is hidden underground, many of the impacts on groundwater-dependent ecosystems are likely to be less obvious and less understood.

Status and Trends

Extent and major uses of groundwater

Approximately 27% of metered water use in NSW comes from groundwater sources. Together, domestic use (including for drinking) and watering stock consume around 17% of the total estimated groundwater drawn from metered NSW groundwater systems. More than 260 towns and villages use groundwater for their reticulated water. For 180 of these, groundwater is their principal water supply source.

Agriculture is by far the greatest user of groundwater in NSW. Most of this water provides irrigation along inland floodplains underlain by high quality alluvial groundwater systems.

Although groundwater is also used in some mining operations, for others it is an obstruction or hazard to be extracted before mining can proceed.

Groundwater resources in NSW

The groundwater found throughout the NSW landscape ranges in depth and salinity and this affects its availability to the environment or suitability for extractive users. The upper groundwater-bearing zone, or water table aquifer, is typically the most important source for groundwater-dependent ecosystems and groundwater's connection with surface water.

Climate, topography and permeability of the host geology strongly influence groundwater resources. In higher rainfall areas in eastern NSW, groundwater tends to be shallower and salinity lower; depth and salinity increase going westward, where evaporation rates are higher and the topography flatter. However, in far south western NSW groundwater outflow causes water levels rise with saline groundwater entering the rivers or forming salt lake complexes on the surface.

The various types of groundwater systems also differ in their yields:

- unconsolidated sediments in alluvial floodplains and coastal sand beds provide the greatest groundwater supplies because they are more permeable

- consolidated porous rocks in the sedimentary basins have varying groundwater yields and salinity from freshwater in the Great Artesian Basin to higher salinity groundwater in some coal basins

- fractured rock groundwater systems typically have low groundwater yields although basalt aquifers on the NSW north coast are among the notable exceptions.

Levels of groundwater extraction and recharge

Only inland groundwater sources are currently metered in NSW. These sources include high-yielding aquifers with good quality water used extensively for irrigation. About 95% of all metered groundwater extracted in NSW comes from inland alluvial systems with the rest from porous and fractured rock systems.

Six major inland alluvial systems account for about 94% of all metered groundwater use in NSW:

- Gwydir alluvium (3%)

- Namoi alluvium (19%)

- Macquarie alluvium (7%)

- Lachlan alluvium (18%)

- Murrumbidgee alluvium (36%)

- Murray alluvium (11%).

Figure 19.1 shows extraction volumes from the metered alluvial, porous and fractured rock systems in NSW between 2001–02 and 2019–20. It reveals two extraction peaks, in 2002–03 and 2018–19, during periods of particularly acute droughts when surface water availability was extremely low.

Figure 19.1: Annual levels of groundwater extraction from metered groundwater systems in NSW 2001–02 to 2019–20

Notes:

LTAAEL = long-term average annual extraction limits

Groundwater extraction remained high during the millennium drought between 2001 and 2009 when access to surface water was limited. Extraction was at its lowest in 2010–11, following the record rainfalls of the 2010 La Niña year. Groundwater extraction gradually increased from then, reflecting greater demand during a period when rainfall and surface water availability were again low. Between 2014–15 and 2016–17, groundwater extraction gradually declined as rainfall and surface water availability improved. In the following three years, groundwater extraction again increased to a new high in 2018–19 due to scarce surface water as a result of another severe drought.

The quantity of groundwater extracted from 12 sources fluctuates around levels close to the extraction limits set in their water sharing plans. In three of these groundwater sources, extraction exceeded the water sharing plans’ compliance trigger and management action was taken to return the extraction back to the plan limit. Nevertheless, the total quantity of groundwater extracted from all metered sources in NSW is well within the combined limit set by their plans.

Long-term average annual extraction limits

Climate variations affect how much groundwater people use. Groundwater is managed on a long-term average basis, an approach that ensures groundwater systems, with their large storage capacities, provide a buffer to supply water in times of drought. During droughts, groundwater extraction may increase to offset the low availability of surface water and groundwater levels decline. In periods of high rainfall, demand for groundwater decreases and this allows groundwater levels to recover, sustaining a reliable and secure water resource.

Water sharing plans define the long-term average annual extraction limit (LTAAEL) for each groundwater source. This is the volume of groundwater that can be extracted on an annual average basis over the longer term and is effectively the plan limit.

The extraction limit in some large inland alluvial groundwater sources is guided by numeric groundwater models. By simulating groundwater flow over many years, these models provide insights into how groundwater systems respond to climate variations and pumping stresses. In other inland alluvial groundwater sources, previous levels of groundwater extraction are used to set the extraction limit, and this controls any growth in groundwater pumping.

In many coastal groundwater systems, the limit simply corresponds to current levels of entitlement. Extraction limits in the remaining groundwater systems are based on allowing a portion of the estimated long-term average rainfall recharge to be extracted each year.

All water not explicitly permitted for extraction is reserved as environmental water. This reserve protects important environmental assets and ensures groundwater sources remain viable over the long-term.

Water sharing plans and extraction levels

Water sharing plans set the rules for allocating local water for various uses: the environment, town water supplies, basic landholder rights and commercial uses (such as irrigation). These plans manage extraction to the LTAAEL. The plans allow groundwater to be extracted for some years at higher volumes than the LTAAEL, which provides operational flexibility to deal with seasonal variations, particularly during droughts.

To manage compliance with the LTAAEL, each water sharing plan sets rules for groundwater use. These rules aim to prevent annual groundwater extractions from exceeding the LTAAEL by a set percentage over a rolling average period. If extraction exceeds this, the plan allows for reductions in available water determinations (AWDs) for aquifer access licences (AAL) or a reduction on taking water from the water accounts (maximum water account debit), or combination of both. This reduces access to groundwater works to bring groundwater extraction back to the LTAAEL.

Temporary water restrictions have also been applied when groundwater levels decline to the point where unacceptable levels of drawdown or GDE degradation is likely to occur.

The first inland groundwater sharing plans progressively reduced access over the 10 years of the plans to bring the historical high levels of groundwater extraction down to the long-term limits for these plans. These included groundwater sources in the Lower Gwydir, Upper and Lower Namoi, Lower Macquarie, Lower Lachlan, Lower Murrumbidgee and the Lower Murray. This entitlement reduction process was completed in 2015–16.

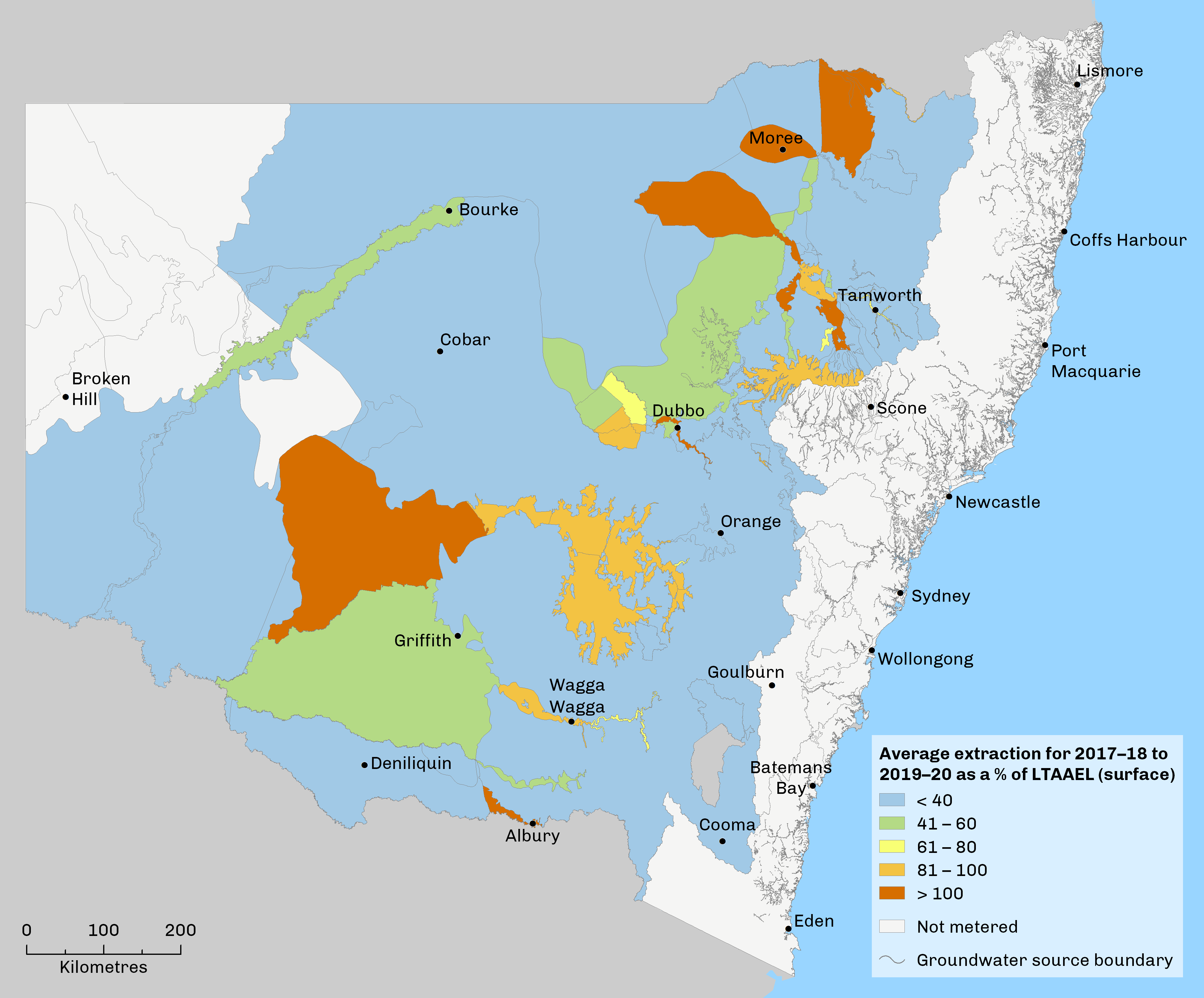

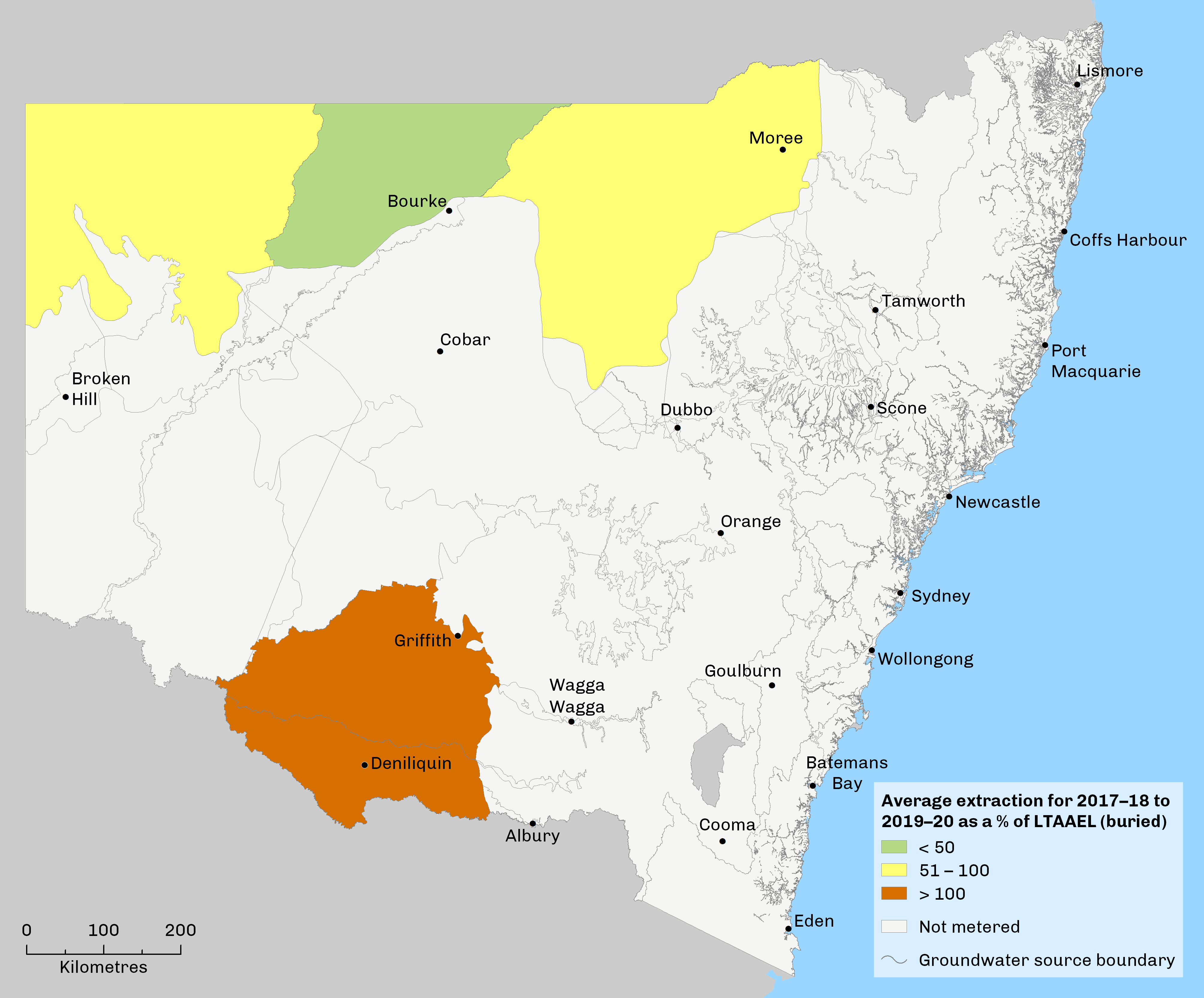

Maps 19.1 and 19.2 show average groundwater use as a percentage of long-term average annual extraction limits for the period between 2016–17 and 2019–20, for uppermost and buried groundwater sources respectively, in areas where groundwater use is metered.

Map 19.1: Extraction from NSW surface groundwater sources as a percentage of the long-term average annual extraction limit 2016–17 to 2019–20

Notes:

Only areas where groundwater use is metered are shown on the map.

Map 19.2: Extraction from NSW buried groundwater sources as a percentage of the long-term annual extraction limit 2016–17 to 2019–20

Notes:

Only areas where groundwater use is metered are shown on the map.

Water resource plans

The Commonwealth Basin Plan 2012 for the Murray–Darling Basin required NSW to develop 11 water resource plans for groundwater. These plans were submitted to the Murray–Darling Basin Authority in July 2020 for accreditation. The fundamental role of the plans is to ensure the implementation of sustainable diversion limits (SDLs) set by the Basin Plan from 2019 and beyond.

Water resource plans set out arrangements to:

- share the water used for consumption

- establish rules to meet environmental and water quality objectives

- account for potential and emerging risks to water resources.

See the topic for more details on the plans.

Aboriginal significance of groundwater

The understanding Aboriginal people have of connected water through thousands of generations of observation is something to celebrate, especially knowing that deep groundwater, such as in the Great Artesian Basin, is very old or ancient water.

Groundwater-dependent culturally significant sites range from under the ground surface to discharging sites into rivers or springs. There are also a range of groundwater-dependent cultural values () and ().

Groundwater-dependent ecosystems

Water sharing plans describe groundwater-dependent ecosystems as ‘ecosystems where the species composition or natural functions depend on the availability of groundwater’. These ecosystems depend completely or partially on groundwater, such as during periods of drought when surface water is not available. The degree and nature of their dependency influences how much these ecosystems are affected by changes to groundwater quality or quantity.

Groundwater-dependent ecosystems (GDEs) are found in a wide range of environments, from highly specialised subterranean ecosystems to more generally occurring land, freshwater and marine ecosystems (). Seven broad types of GDEs, falling into two main groupings, are defined according to their ecology, geomorphology and water chemistry as below.

Subsurface ecosystems:

- subsurface phreatic aquifer ecosystems

- karsts and caves

- subsurface baseflow streams.

Surface ecosystems:

- surface baseflow streams

- wetlands

- estuarine and near-shore marine ecosystems

- groundwater-dependent or phreatophytic vegetation.

Underground springs and cave systems host the most significant, diverse and potentially sensitive groundwater-dependent ecosystems and organisms.

Identifying groundwater-dependent ecosystems

Ongoing work under the NSW State Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Policy () is identifying and describing GDEs across the state to improve understanding of them. Current mapping, completed statewide, is available through the Bureau of Meteorology’s Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Atlas, and the NSW SEED portal which provides the latest dataset of GDEs. The NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment also reports on the extent of groundwater-dependent ecosystems across the state and assesses their ecological value.

Pressures

Excessive demand and extraction

Reducing the storage levels of a groundwater source or consistently mining its water resource beyond the recharge rate affect its long-term integrity. This has permanent consequences for all dependent ecosystems and beneficial uses. Competition for groundwater resources can place the long-term security of these resources at risk.

Saline intrusion and groundwater quality

Intrusion of salty water into aquifers has detrimental effects on water quality and related uses. Saline intrusion can be high risk where:

- groundwater extraction is high

- the aquifer is overlain or underlain by saline aquifers

- the aquifer is near the coast.

Coastal sand beds north of Newcastle exemplify the risk of saline intrusion in this important water source for Greater Newcastle. To manage this risk, bore monitoring sites have been constructed along several transects in the Tomago and Tomaree water sources to monitor for changes in seawater intrusion. Each bore has specific triggers linked to response procedures under the Hunter Water Corporation’s Sustainable Groundwater Extractions Strategy.

Further north, in the Stuarts Point Water Source, the NSW Government has constructed a series of bores aligned in transects to monitor for seawater intrusion. Each bore uses automatic data loggers to collect hourly salinity data.

Studies of high-volume groundwater extraction in inland alluvial aquifers identified localised areas of water quality decline associated with changing groundwater flow patterns due to the extraction. Strategies are being developed to address these risks.

Chemical contamination

Chemical contamination of groundwater reduces its value for users and the environment and increases water treatment costs. This contamination can even prevent some types of water use altogether. Once polluted, an aquifer is extremely difficult and expensive to restore. An example of this is the Orica chemicals manufacturing facility at Botany in Sydney. Decades of poor management practices contaminated the surrounding soil and groundwater with chemicals such as mercury and hexachlorobenzene, rendering the groundwater unusable for residential purposes. Orica is now working at remediation of these legacy contaminants.

Groundwater contamination is largely associated with areas of longstanding industrial activity (existing or former). Such areas are found around Sydney, Newcastle and Wollongong. However, groundwater contamination can also occur in regional areas, for example where there have been leaks from underground petroleum storage systems or septic tanks.

Various levels of groundwater contamination have been reported in a number of locations across NSW as a legacy of the use of foams containing per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for firefighting until 2007. The chemical characteristics of PFAS make them highly resistant to degradation. Consequently, PFAS compounds may persist in environmental media, such as soil, sediments, surface water, groundwater and biota for many years after the release occurred.

Responses

Legislation and policies

NSW Water Management Framework

The NSW water policy and management framework includes the 20-year NSW Water Strategy the NSW Government has developed to address the key challenges and opportunities for water management and service delivery across the state, and to set the strategic direction for the NSW water sector over the long-term.

The strategy is part of a suite of long-term water strategies including 12 regional and two metropolitan water strategies. A dedicated Groundwater Strategy is also being prepared. The strategies link with water sharing plans which remain the legal instruments for managing water resources in NSW under the NSW Water Management Act 2000. These plans are an important component of water resource plans that the NSW Government has developed as part of its obligations under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan. See below and topic for further information.

Water Management Act 2000

Under the Water Management Act 2000, all groundwater sources must be managed sustainably. Statutory water sharing plans for groundwater are implementing this sustainable management.

Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997

Under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997, contaminated groundwater treatment is considered to be a scheduled activity if it has the capacity to treat more than 100 megalitres per year of contaminated water.

Contaminated Land Management Act 1997

Under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997, groundwater that is contaminated must be reported to the Minister administering the Water Management Act 2000.

NSW State Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Policy

The NSW State Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Policy () has guidelines on how to protect and manage GDEs. Ongoing work seeks to improve understanding of the location of these ecosystems and determine the extent of their reliance on groundwater.

NSW Aquifer Interference Policy

The NSW Aquifer Interference Policy () details how to assess and license water take from and potential impacts to aquifers, such as mining and coal seam gas (CSG) extraction activities. It aims to balance the water requirements of towns, farmers, industry and the environment. The policy plays an important role in assessments for proposed mining and CSG developments. Because the aquifer interference approval provisions of the Water Management Act have not been enacted, some groundwater-related activities are still administered under the Water Act 1912.

Programs

Regional water strategies

The NSW Government is preparing comprehensive regional water strategies that will bring together the latest climate evidence (see Climate Change section) with a wide range of tools and solutions to plan and manage each region’s water needs over the next 20 to 40 years.

The NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment is developing 12 regional water strategies in partnership with water service providers, local councils, Aboriginal peak bodies, communities and other stakeholders.

NSW Groundwater Strategy

As part of its suite of water strategies, the NSW Government is developing a NSW Groundwater Strategy. A draft is proposed to be released for public exhibition in mid-2022.

Water sharing plans

Water sharing plans are important tools to manage groundwater in NSW. They provide for better management of water extraction practices and protect a proportion of recharge for the environment. Water sharing plans developed for all NSW water sources were in place by the end of 2018. The plans are reviewed every 10 years, at which time they are either remade or renewed.

Under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan, water sharing plans underpin 11 water resource plans for groundwater. See topic.

Water resource plans

The NSW Government has developed water resource plans as part of implementing the Murray–Darling Basin Plan. Water resource plans are a key feature of the Basin Plan which provides a framework to integrate the basin's water resource management over the long-term. Water resource plans align basin-wide and state-based water resource management. They recognise and build on existing water planning processes.

Each water resource plan has:

- the relevant water sharing plan

- a long-term environmental water plan

- a risk assessment

- a water quality management plan

- an incident response guide to deal with periods of drought and poor water quality.

In NSW, 11 water resource plans have been developed for groundwater resources following three years of public consultation and discussion with stakeholders and the community. They are currently in the process of being assessed and reviewed by the Murray–Darling Basin Authority. See topic.

Water quality management plans

As required by the Murray–Darling Basin Plan, water quality management plans have been developed for all NSW basin areas with water resource plans.

Each water quality management plan:

- establishes water quality objectives and targets for freshwater-dependent ecosystems, irrigation water, and recreational uses

- identifies key causes of water quality degradation

- assesses risks from water quality degradation

- identifies measures that help achieve water quality objectives.

Improving Great Artesian Basin drought resilience (Cap and Pipe the Bores Program)

Since the 1990s, various programs have sought to reduce the waste of water and improve groundwater pressure by capping and piping bores across the NSW part of the Great Artesian Basin.

The Cap and Pipe the Bores Program provides financial incentives for landowners to offset the costs of replacing uncapped artesian bores and open drains with rehabilitated bores and efficient pipeline systems. These pipeline systems provide water to properties, prevent large quantities of salt from entering drainage systems and help drought-proof properties. The program's measures have produced water savings of 80,300 megalitres annually in the NSW Great Artesian Basin and water pressure across the basin has increased. A further joint Commonwealth–NSW Government phase of the program, 'Improving Great Artesian Basin drought resilience', was announced in 2019 for a five-year period.

The 2020 NSW Great Artesian Basin Water Sharing Plan enables 30% of the current and future water savings under the Program to be available for extraction under the LTAAEL in the Surat, Warrego and Central water sources.

Metering

Extraction from coastal groundwater sources is not currently metered. Under the NSW Non-Urban Water Metering Policy (), licensed works with a diameter of 200 mm or larger, or those which extract water from at-risk groundwater sources need to be fitted with an accurate meter and a telemetry-capable data logger. The metering requirements for groundwater works will be rolled out first in the inland northern region by December 2021, followed by the inland southern and coastal regions by December 2022 and December 2023, respectively. These measures will make data on water take and reporting more timely and efficient.

Identification of groundwater-dependent ecosystems

Two key stages of work to better identify the state’s GDEs have been completed. Firstly, the Department of Primary Industries released comprehensive mapping of high-probability NSW GDEs based on a research report, Methods for the Identification of High-probability Groundwater Dependent Vegetation Ecosystems ().

Secondly, high-probability GDEs have been prioritised according to their ecological value, allowing their better management. Methods used to assign them are based on the High Ecological Value Aquatic Ecosystem (HEVAE) framework (). This work identified a subset of high-probability, high-value GDEs across NSW. Managers are now able to consider the risks to these GDEs posed by water extraction and determine whether controls are required to manage these risks, as well as whether more monitoring or information is needed.

Future opportunities

Some groundwater sources have unassigned water available, which means that the level of commitment under basic landholder rights and access licences is less than the water sharing plan extraction limit. In these systems, the Minister for Water can make water available under a controlled allocation process for consumptive use.

Most extraction from coastal groundwater sources is not currently metered. Non-metered take of groundwater also presents opportunities for better measuring, modelling and hydrometrics. Under the NSW Non-Urban Water Metering policy, meter coverage will improve across the state. Better monitoring of water extracted will improve understanding of how groundwater systems respond to climatic and pumping stresses.

Knowledge of groundwater-dependent ecosystems is still emerging. Better understanding of their location, characteristics and levels of dependency on groundwater is needed. Little is known about plants and animals living within, or dependent on, groundwater aquifers. These knowledge gaps make it difficult to manage groundwater systems in ways that will ensure their protection. And with such a strong Aboriginal connection to groundwater, NSW water managers must protect its quality and quantity from impactful drawdown, pollution from industry, mining and agriculture and over-extraction to ensure cultural values of groundwater are protected.

References

DLWC 2002, NSW State Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Policy, Department of Land and Water Conservation, Sydney